Quiet Instruments

Noguchi Tunes Water and Stone into Welfare and Health at Chase Manhattan Bank

Feature photo from here

Originally submitted as part of the curriculum at Thomas Jefferson University | October 4, 2025

Presented at the 32nd Japan Studies Association conference, Honolulu, HI | January 2026 | Program TBD

Introduction

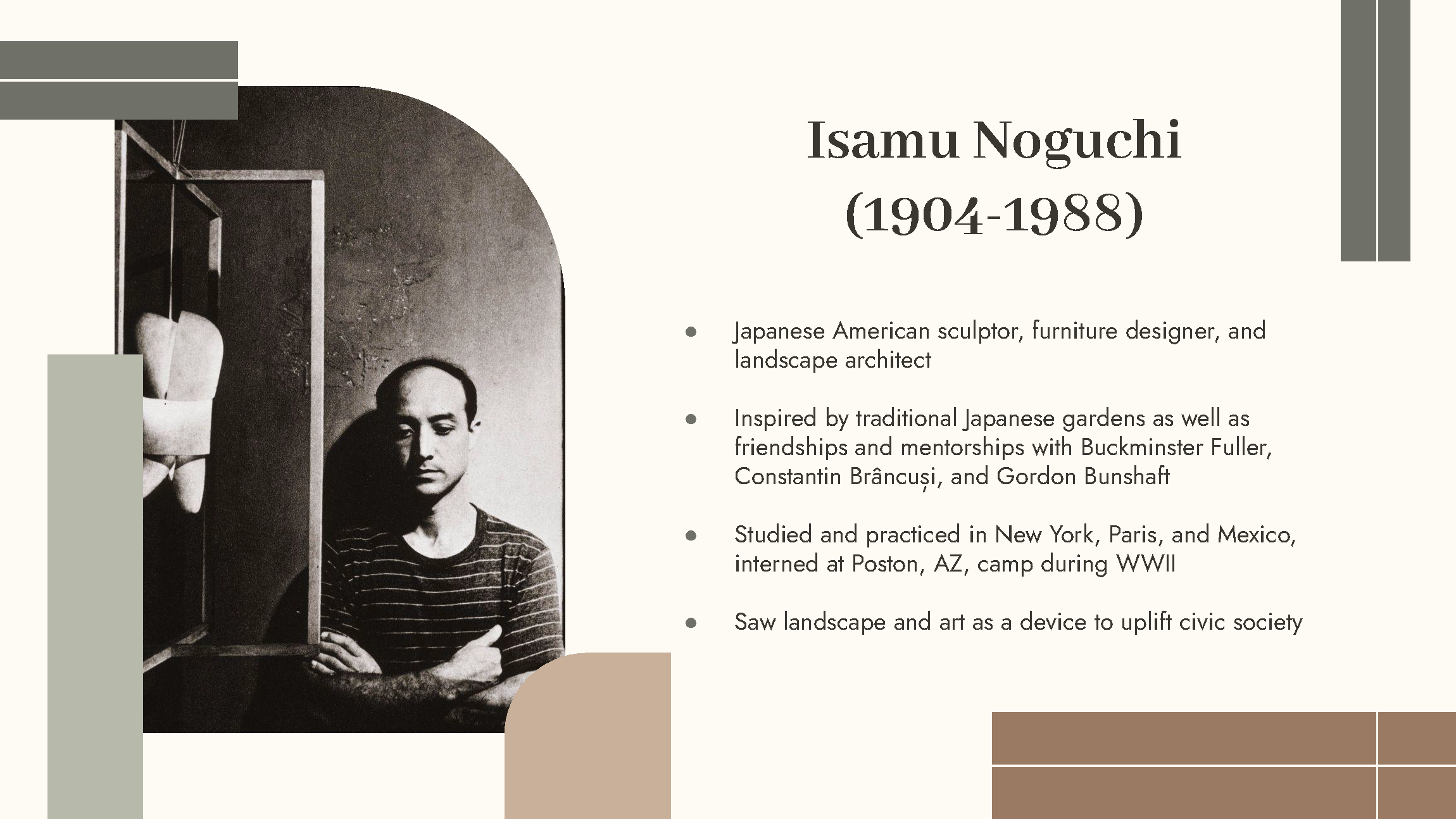

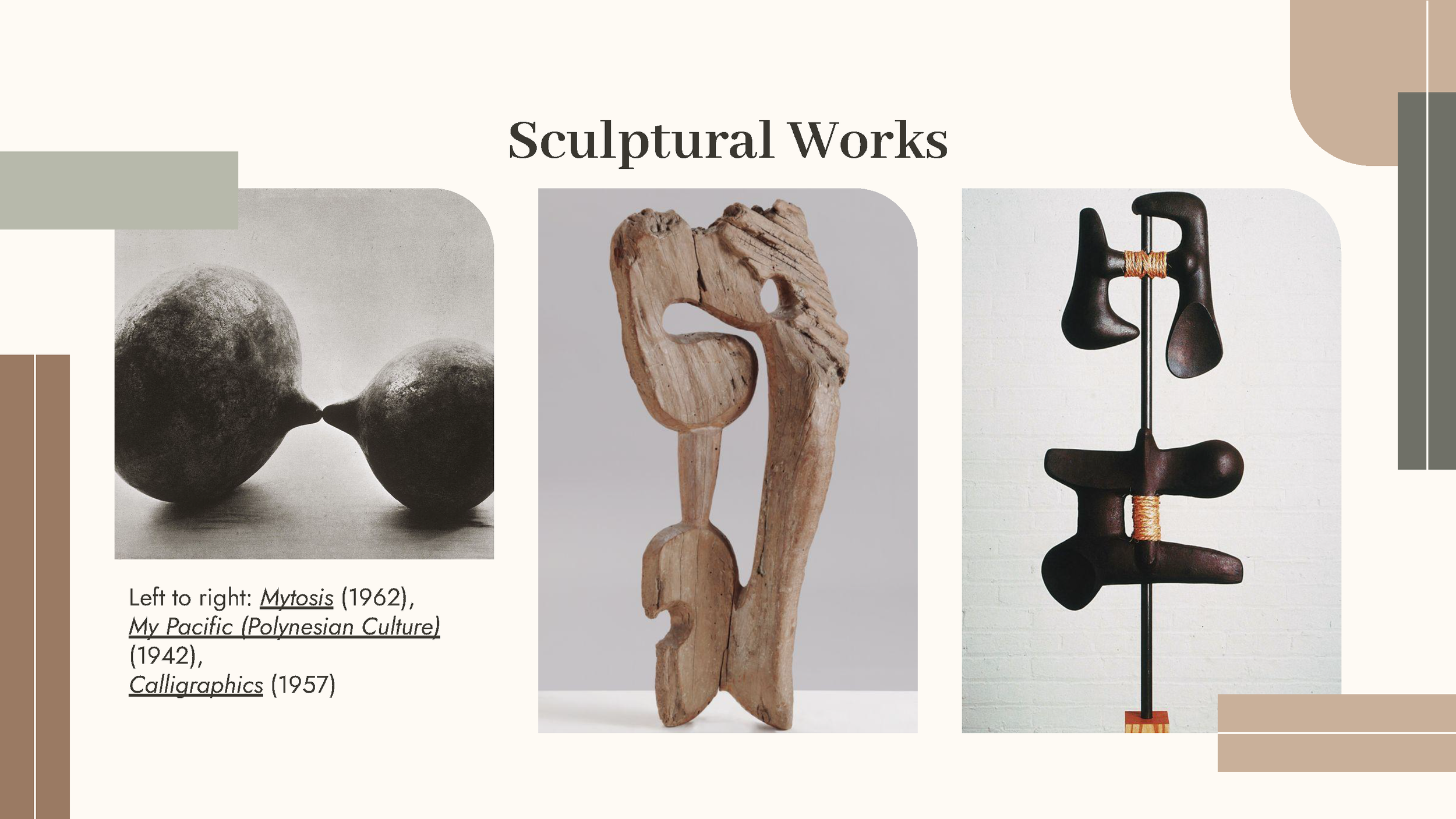

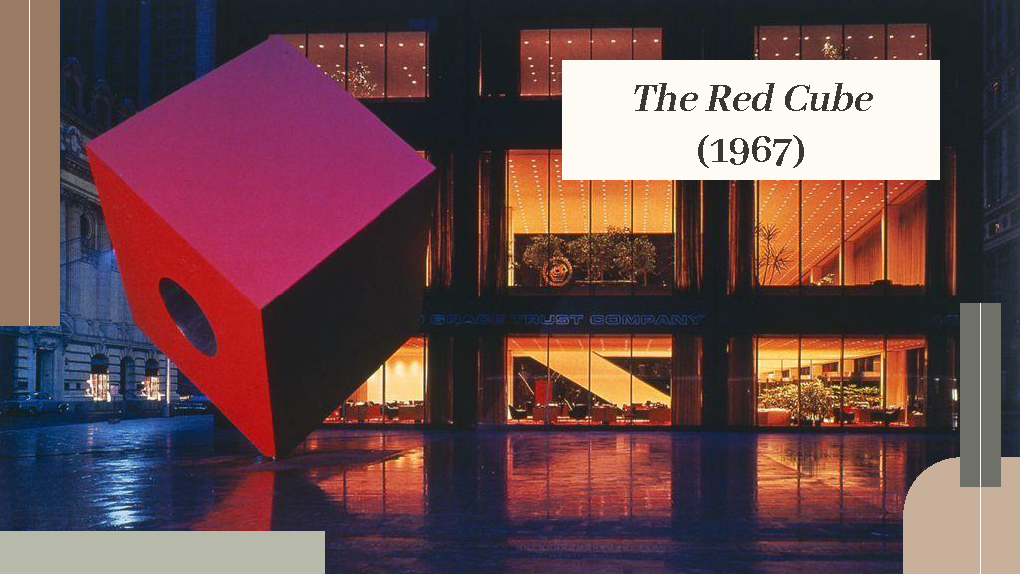

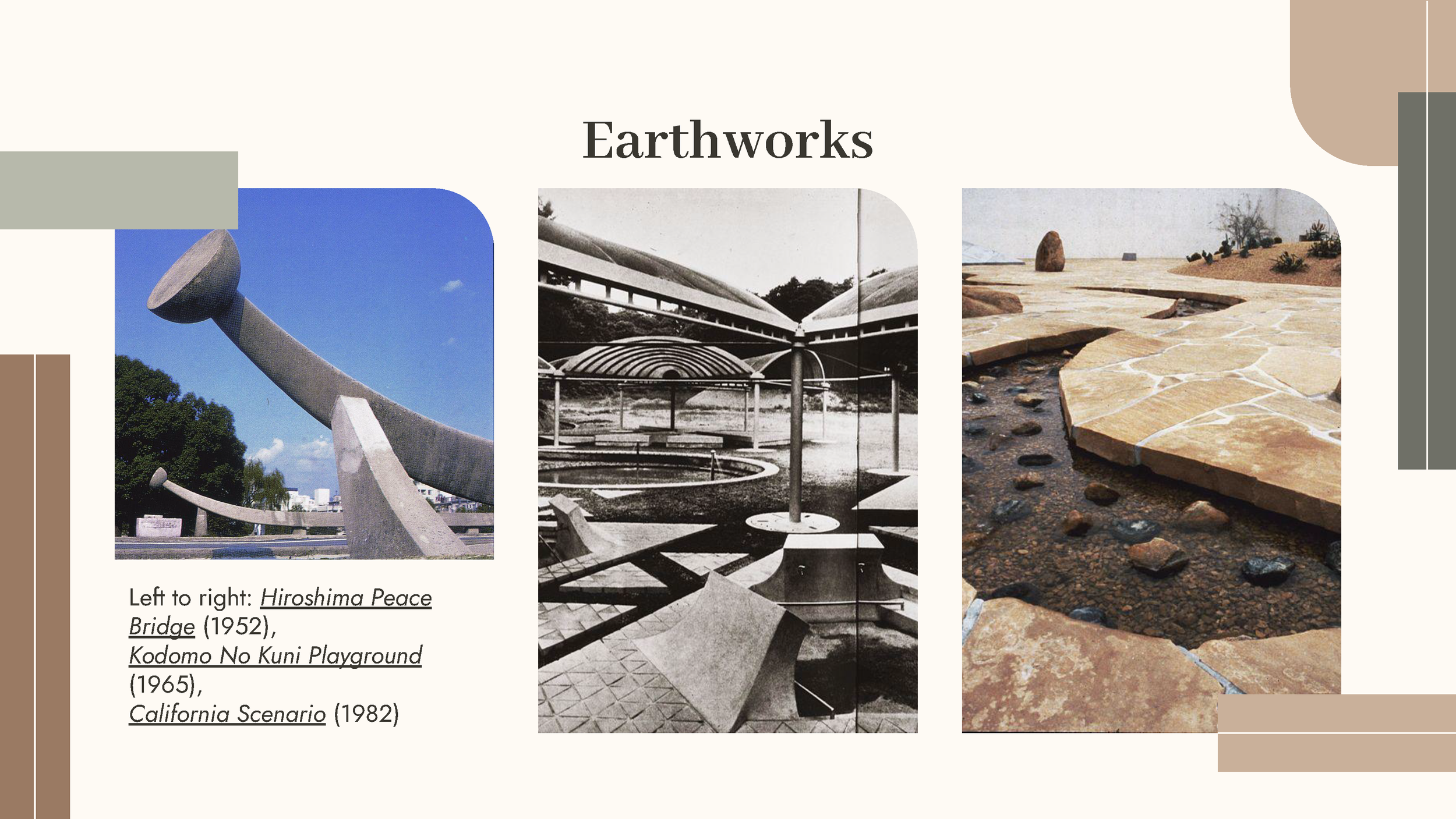

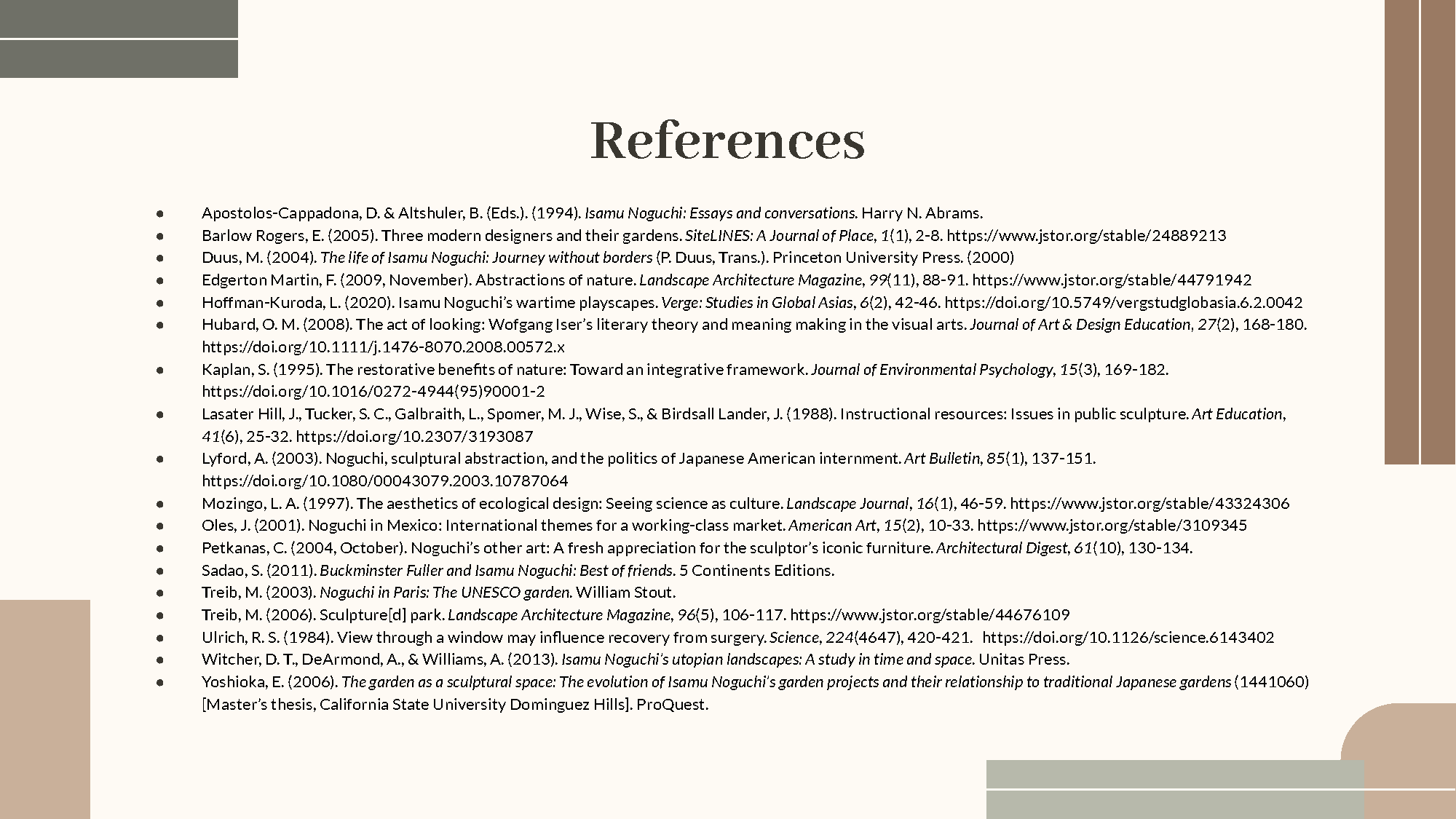

Isamu Noguchi (1904–1988) moved between worlds and mediums, shaping space with a sculptor’s intuition and a landscape architect’s patience. Trained in stone and schooled by choreography and theater, he learned to think in systems rather than isolated objects and to treat movement as structure (Duus, 2004; Apostolos-Cappadona & Altshuler, 1994). Scaled to the city, those studio habits, clarity of figure, choreographed experience, and materials that keep time, became the ground of his gardens and social public rooms. His range spread from the elegant tactility of the Noguchi table and Akari lamps to urban set pieces like Red Cube and environmental works such as the UNESCO garden in Paris and the sunken courts at Yale and in Lower Manhattan (Petkanas, 2004; Treib, 2003; Duus, 2004).

Landscapes extend these lessons into civic practice. Clarity of plan aligns with the choreography of looking and walking, while stone and water act as exemplary processes rather than pictures (Apostolos et al., 1994; Duus, 2004). He put it plainly: “I claim the whole garden is a sculpture,” a single field that organizes use rather than a collection of objects that command it, and he insisted on designing for the community, recognizing the artist as a public servant so “individual possession has less significance than public enjoyment” (Hoffman-Kuroda, 2020; Apostolos et al., 1994, pp. 71, 26).

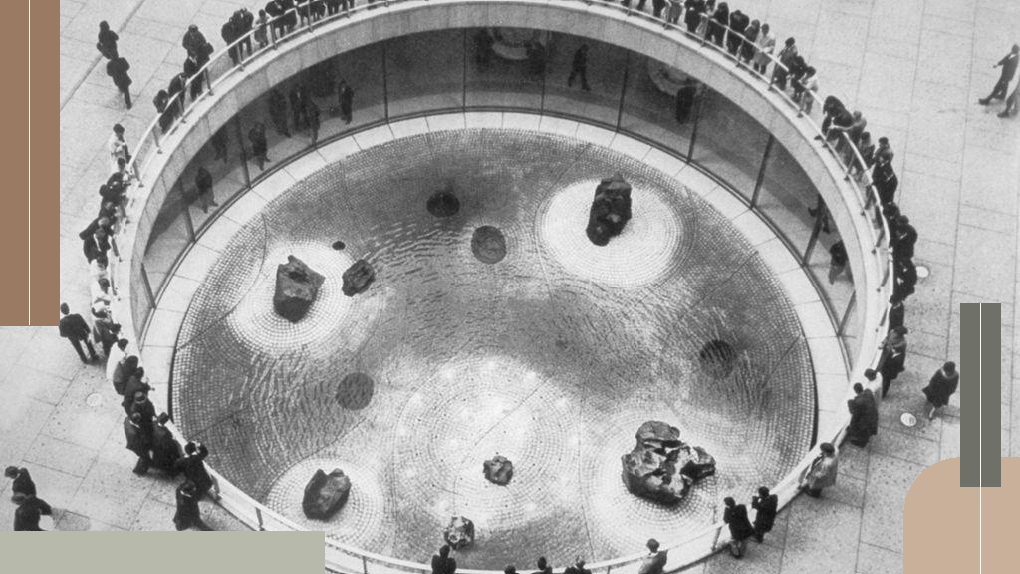

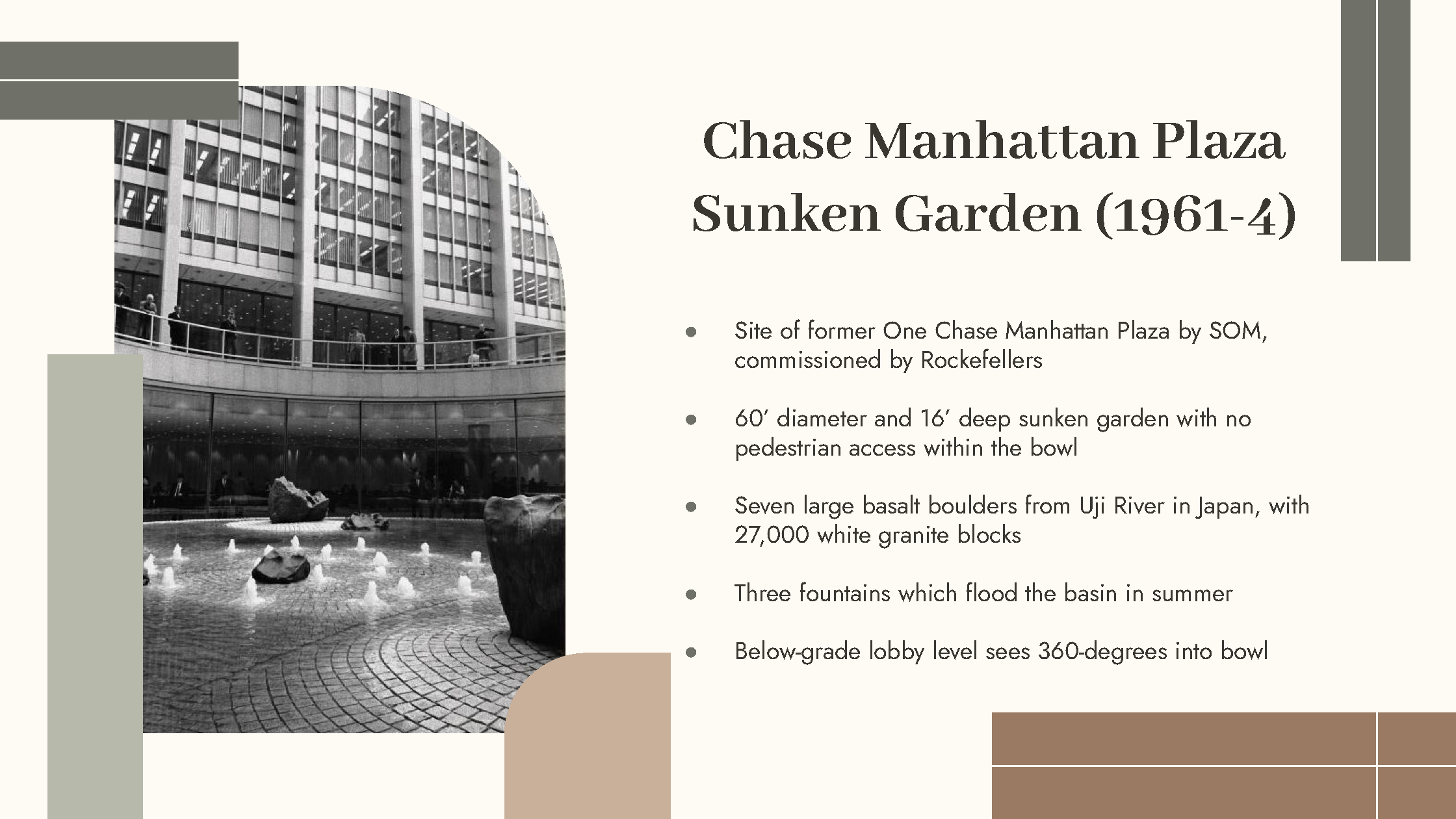

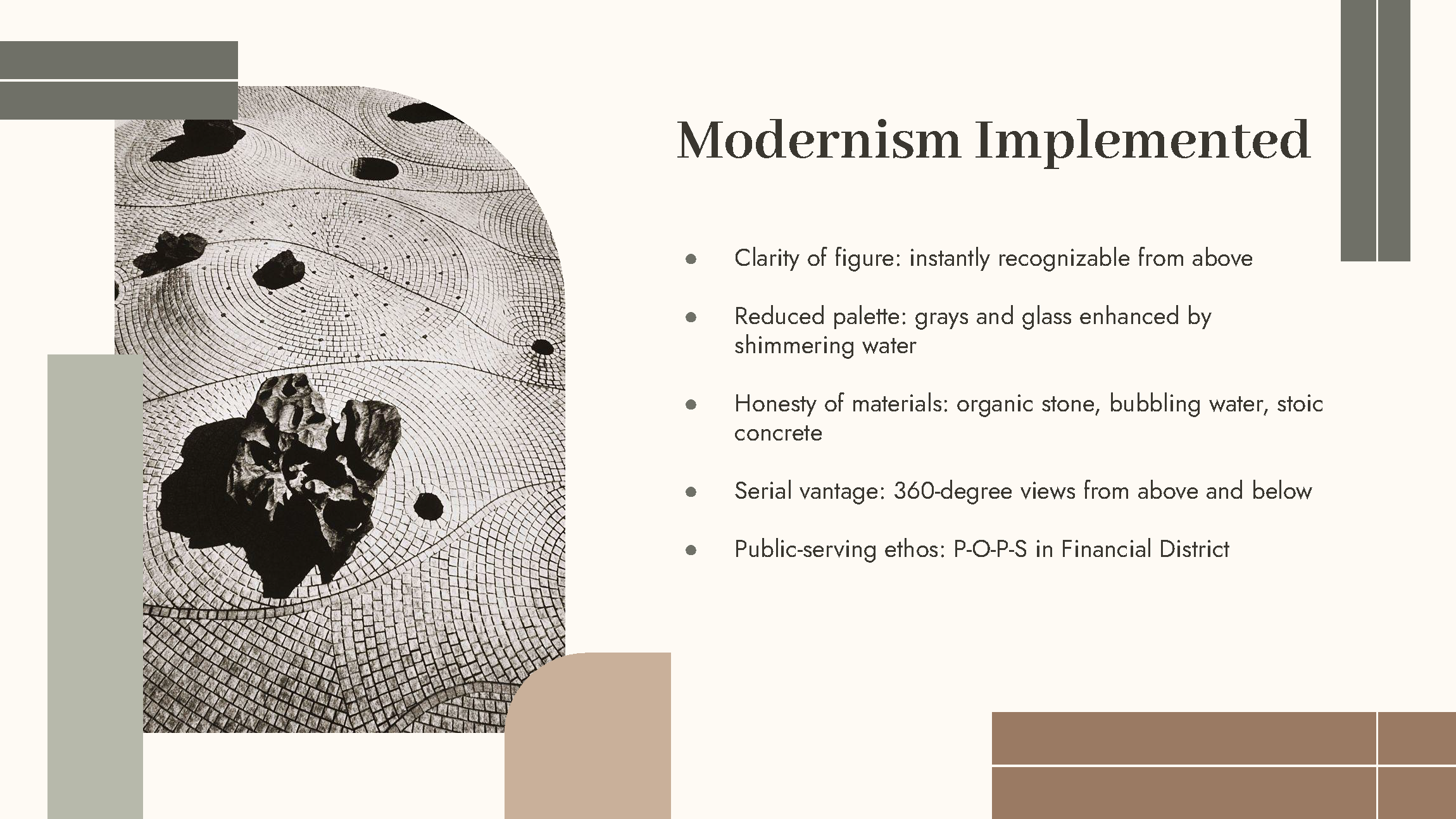

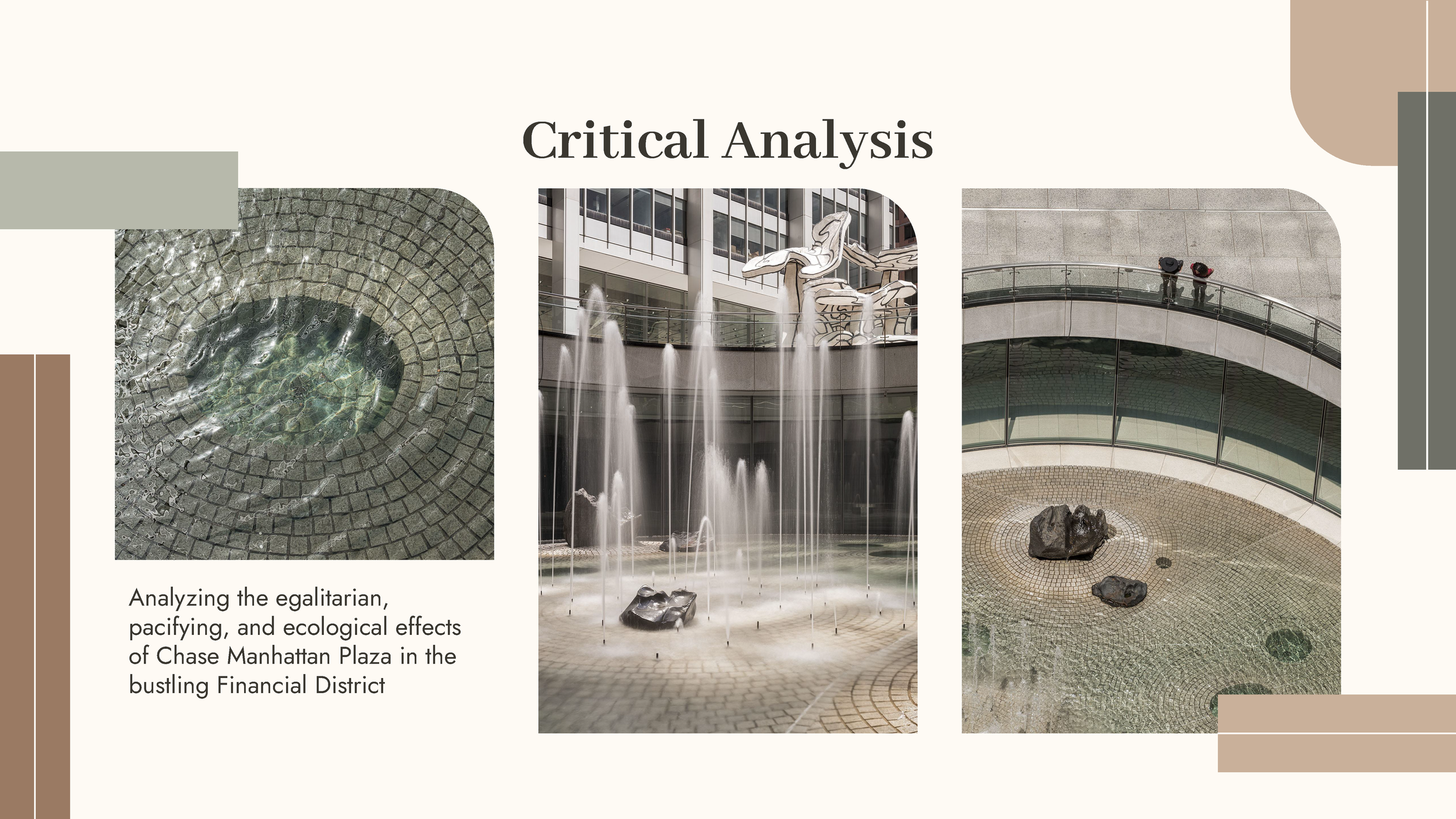

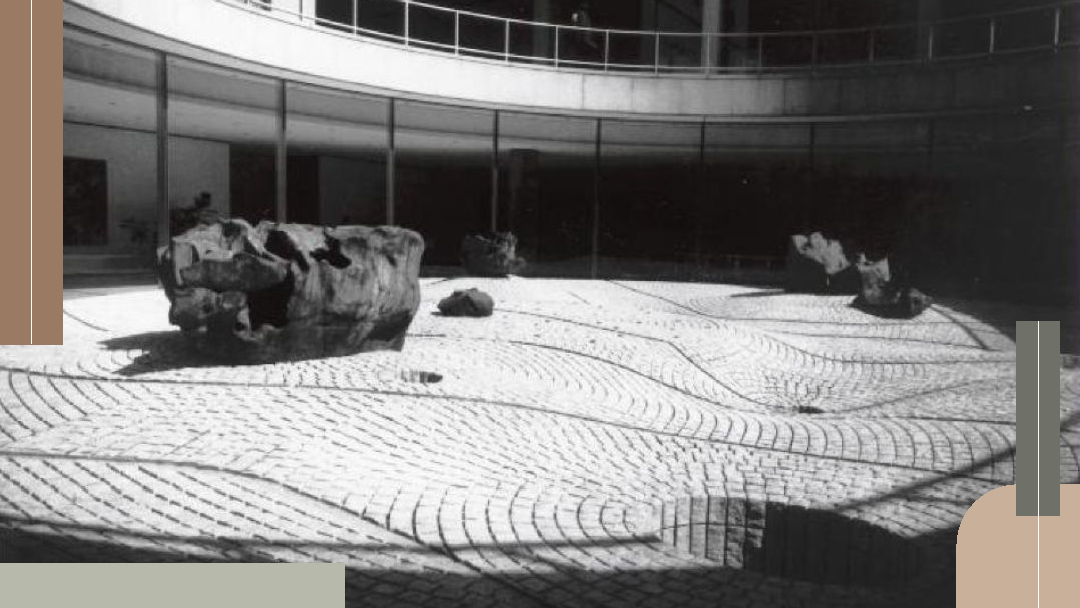

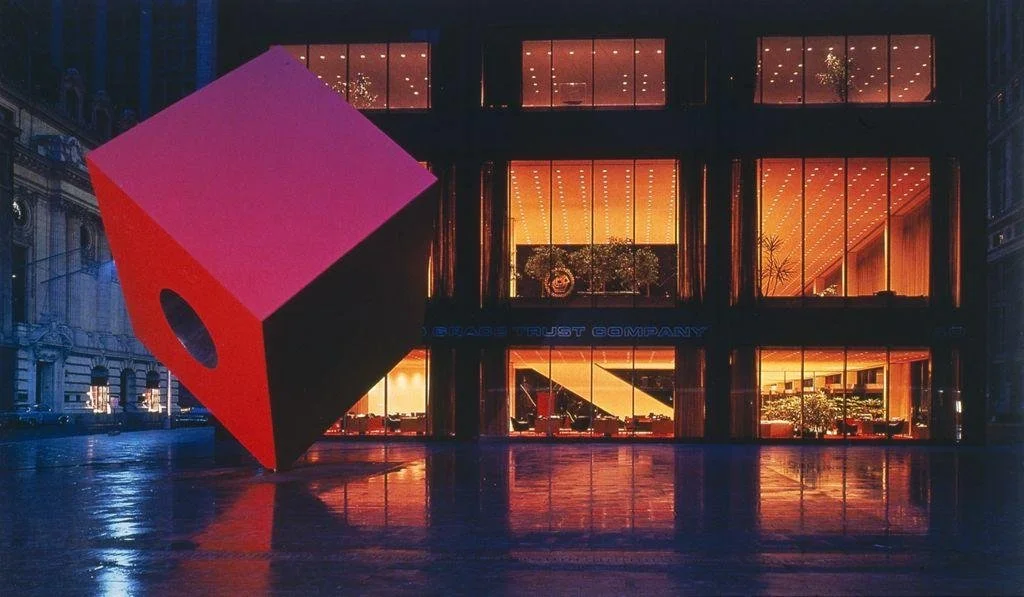

Chase Manhattan Sunken Garden (1961–64) concentrates this method. A circular figure invites roaming along the rim rather than frontality; a lowered bowl sets dual vantage from street and lobby; stone and seasonal water carry most of the expression (Yoshioka, 2006). At Chase, Noguchi expertly wields Modernist clarity with intentional hydrological processes and temporal natural materials to lower social friction and hierarchy, encourage analgesic responses in bustling Manhattan, and elevate the ecological microclimate of the concrete city, each acting both separately and reinforcing one another in and around the bowl park (Yoshioka, 2006; Treib, 2003; Treib, 2006; Ulrich, 1984; Kaplan, 1995; Mozingo, 1997).

-

Sunken Garden (1961-64) at Chase Manhattan Bank Plaza, New York, NY (Falk, 1964)

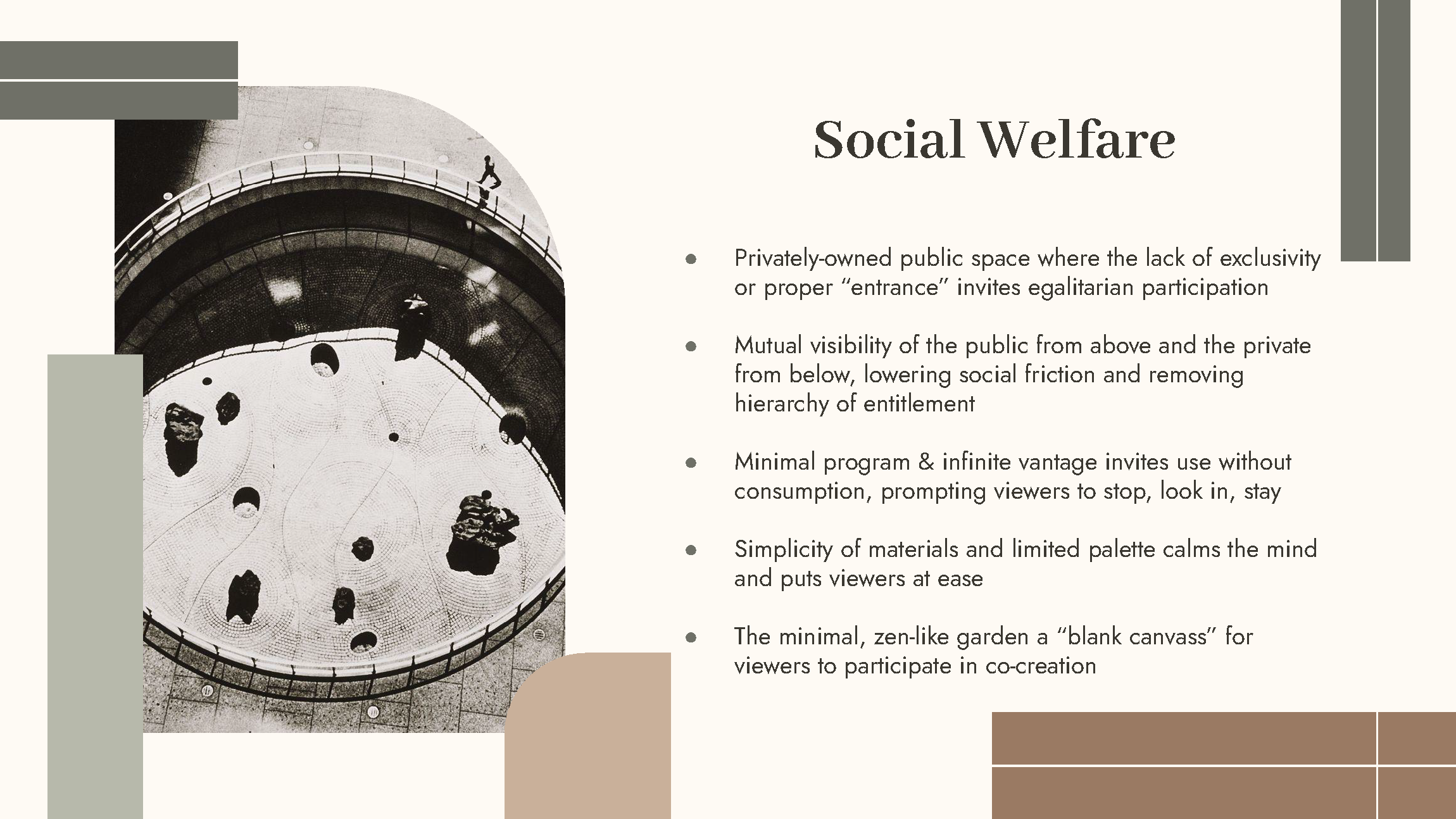

Social Welfare

Belonging needs a clear invitation, or at least an absence of exclusion. At Chase the circle denies a front and distributes attention around the entire streetscape, seen just from the edges above or below. But there is still room to roam, below grade in the glass lobby, so this corporate threshold transforms into a shared ground in Lower Manhattan’s privately owned public space network, with visitors occupying the balcony or lobby rather than the interior of the garden (Yoshioka, 2006). Noguchi’s own language underwrites the choice: a garden composed as sculpture (Apostolos et al., 1994; Hoffman-Kuroda, 2020), made for interaction through sight, acting as a museum piece presented on pedestal, to be appreciated from 360-degrees only through the protective glass. Such clarity, however, invites lingering and mutual awareness rather than spectacle at distance, lowering social temperature at the parapet and making casual occupation feel warranted (Barlow Rogers, 2005).

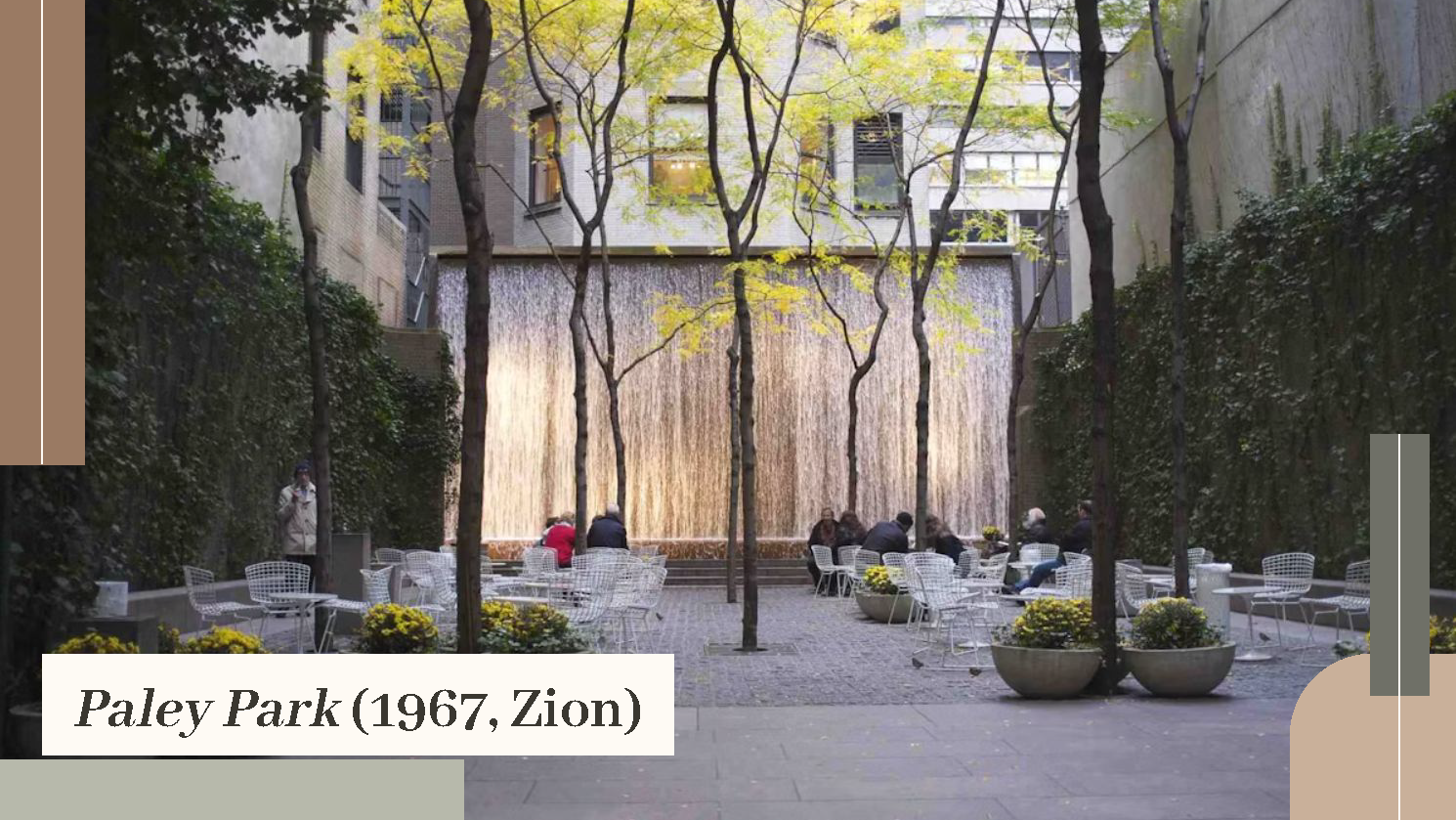

The two vantage points, a public balcony along the street and an interior vantage from the lower lobby, fold passersby, office workers, and visitors into a unified congregation. From the sidewalk, a quick scan takes in the whole bowl and opposite lobby, while people at the rail become part of the scene for others across the way. From underground, the city slides by as a moving proscenium of faces and footsteps. This scenic and humanistic blurring is present throughout Noguchi’s work: at the Beinecke Garden (1960-64) at Yale University, layered spectatorship between terrace and court makes seeing and being seen a routine exchange. At Chase the public above and the bankers below are mirrored. Although the parties are separated by grade, the hierarchy between public and private is eliminated (Apostolos et al., 1994; Treib, 2003; Yoshioka, 2006). In a district coded by access and status, stacked vantage normalizes co-presence among office workers, tourists, and neighbors who might otherwise pass without acknowledgment. Read against the politics of visibility around Japanese American identity, this everyday recognition works to break down the class and racial barriers of the 20th Century, working towards Noguchi’s goal of reintegrating “the arts towards some purposeful social end” (Lyford, 2003; Hoffman-Kuroda, 2020, p. 43).

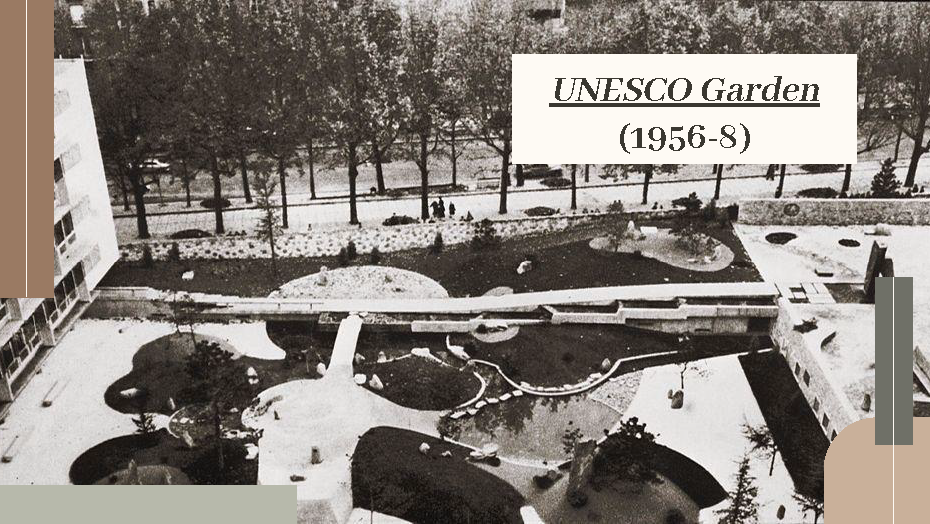

The edge, and its invitation to meander around the entire bowl, gives social cues. Earlier at the UNESCO Garden (1956-58) in Paris, in which one can physically enter, Noguchi composed terrace, path, and lower garden so that walking staged approach and encounter as part of the garden itself (Treib, 2003). Chase, on the other hand, condenses that sequence into a curvilinear promenade at the rim. A short walk along the balustrade, a pause at the parapet, a glance exchanged with viewers across the bowl: the choreography yields recognition and shared occupation without signage or access to the floor (Yoshioka, 2006). Public art pedagogy clarifies that when thresholds and cues are legible, or at the very least barriers remain absent, more people feel entitled to stop, look in, and stay, even on private land shaped to serve the city (Lasater Hill et al., 1988).

There are few physical elements but their structure is evident, echoing the same openness Noguchi refined in smaller sculpture and furniture, putting the viewer at ease. The tripod clarity of the Noguchi table and the luminous restraint of Akari model stability with certainty; at Chase the circle and bowl do analogous work for people along the rail, offering availability rather than control (Petkanas, 2004; Apostolos et al., 1994). In accordance with Iser’s notion of the viewer as co-author, viewers can see the garden near-circular infinite perspectives at each visit, alternating between high and low, the bowl dry and stoic or deluged and reflective, from any degree around the bowl, supplying a blank canvass that pedestrians complete through looking and return visits (Hubard, 2008). Plan removes hierarchy, section builds reciprocal seeing, and the parapet becomes a shared stage for everyday public life. What might read as corporate décor performs as an egalitarian civic room at the edge, composed with minimal means and open to the many (Yoshioka, 2006; Barlow Rogers, 2005).

-

The Red Cube (1967) at Marine Midland Building, New York, NY (Stoller, 1968)

-

The Noguchi Table (1944) (Noguchi Foundation, 2007)

Public Health

Relief comes first as physical sensation. In summer the basin fills and bubbles, cooling the air and slowing the block with calming blue ripples that invite brief pauses at the rail and idle looking from the lobby (Yoshioka, 2006). The depressed bowl echoes the babbling fountain, softening the intensity of the traffic and bustle of Manhattan, lightening the mood from hurried utilitarianism to slowed reflection. Environmental psychology links such ordinary contact with nature to measurable benefit: Ulrich (1984) found that a window in view of trees from the inside of hospital rooms hastened recovery, the patients even requiring less analgesic medication. Research into the holistic and medicinal effects of being with nature resulting in reduced stress and pain continues to produce positive findings.

Next, attention steadies, attuned to the frequency of the quiet bubbling echoing throughout the bowl. At the balustrade, even a quick glance comprehends the whole figure, while down below, the lobby view offers a calmer, framed prospect. Attention Restoration Theory (Kaplan, 1995) helps name what visitors feel. Softly fascinating stimuli, a brief sense of being away, coherent extent, and compatibility with intent are linked to the recovery and composure of directed attention even in short visits (Kaplan, 1995). Here rock patterns and shimmering water offer intentional fascination, the clear outline of the bowl creates the form, and the option to look in while passing by or taking a moment to pause at the rail provides access and compatibility. Although the project was primarily composed to be viewed from above (Yoshioka, 2006), the vantage from the below-grade lobby similarly offers a reprieve from emails and spreadsheets.

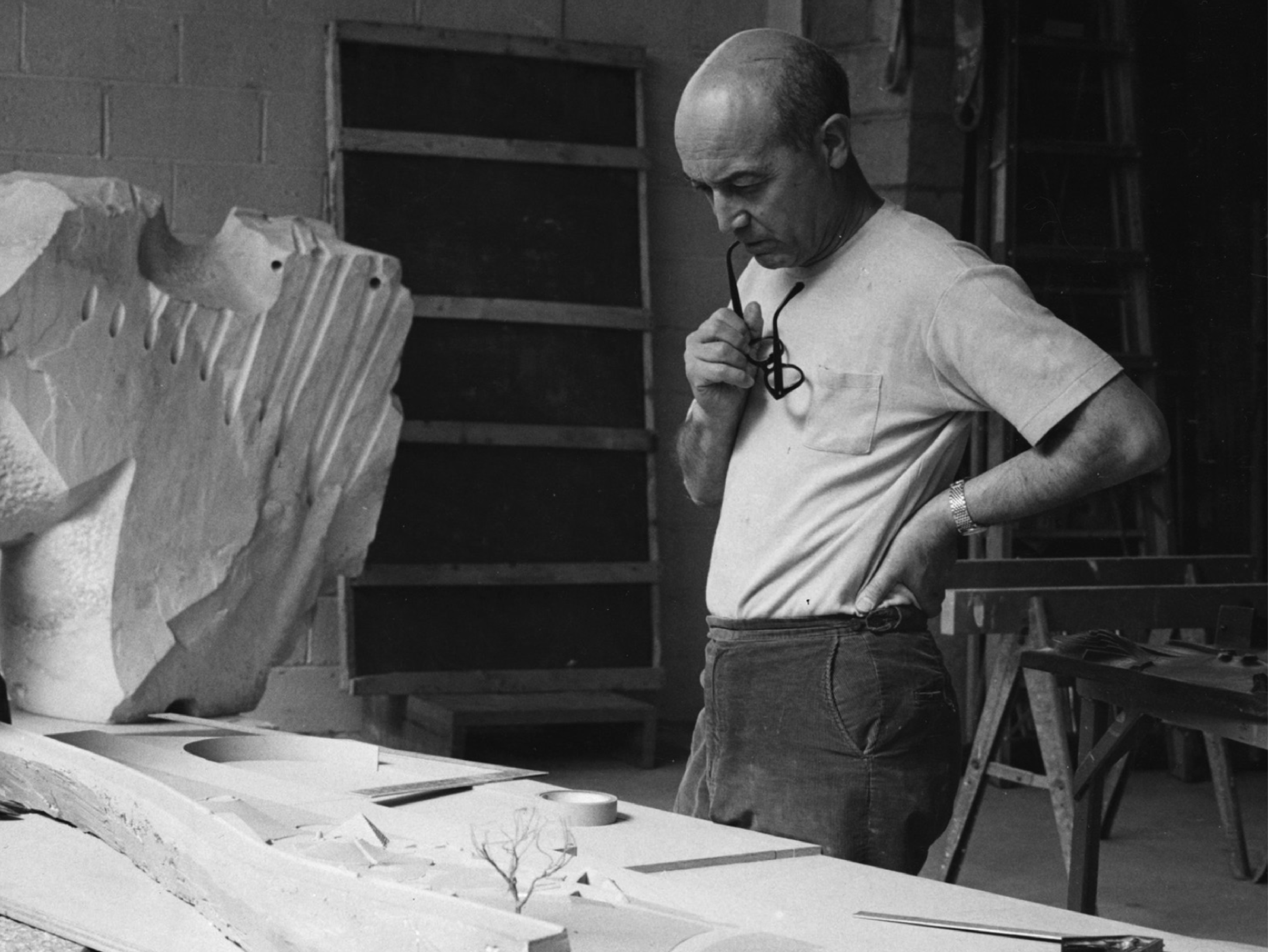

Care extends across seasons, with clear processes: the garden is wet in summer for evaporative cooling and sound masking, but dry in winter for wind calm, crisp views, and steady light on stone (Yoshioka, 2006). This is not incidental comfort but planned public amenity. Earlier playscape proposals show the same civic health instinct, where shade, water, and soft ground are treated as shared infrastructure, scaled here for adults between tasks at an overlook (Hoffman-Kuroda, 2020). In the unrealized designs for Riverside Playground (1961-62) with Kahn, a winter suntrap pairs with summer water play, a thermal strategy echoed at Chase in seasonal form (Witcher, DeArmond, & Williams, 2013). At other gardens, Noguchi explored mist and atomized water to fine-tune cooling, underscoring persistent attention to microclimate (Duus, 2004).

Finally, a simple palette puts the mind at ease so restoration can happen quickly (Kaplan, 1995). A disciplined stone field below, limited planting, and a clear parapet edge make the order of the place instantly legible. Across scales, Noguchi’s landscape designs personify the stone awash in light and weather, keeping the scene coherent and grounded while water shifts state across seasons (Edgerton Martin, 2009; Yoshioka, 2006). When order is grasped immediately and sensory demand is low, short looks suffice for small restorations at the edge. Cooling and masking that the body feels at the parapet, softly fascinating scenes that the mind can rest on, and seasonal operations that keep comfort accessible make Chase a quiet health asset in daily use. Instead of treating patients in sterility, it conditions the workday with repeatable moments of ease that align with biophilic findings while exemplifying Noguchi’s restrained palette but unceasing imagination (Ulrich, 1984; Kaplan, 1995; Yoshioka, 2006; Hoffman-Kuroda, 2020).

-

The UNESCO Gardens (1956-58) aerial view (Noguchi Foundation, c. 1958)

-

The fountains at Expo 170 (1970) in Osaka, Japan (Noguchi Foundation, c. 1970)

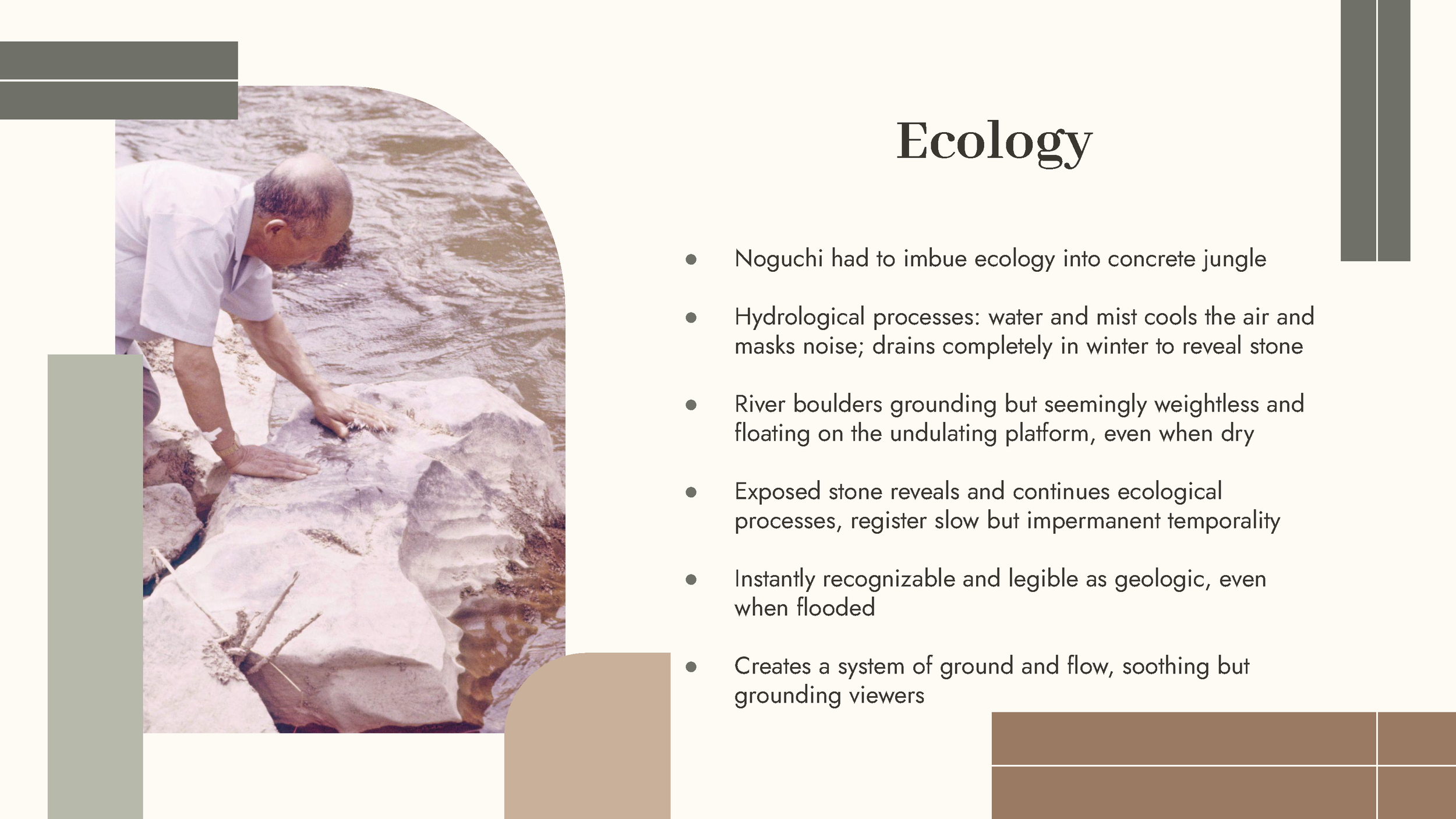

Ecology

Ecology plays a dual role in landscape architecture: the designer must wield it, but also must enact, protect, and enhance it. At Chase, hydrology leads the script: a wet, bubbling basin in summer, cooler and quieter in heat, and an exposed stone desert in winter, clearer and wind-calm in cold (Yoshioka, 2006). Effective ecological design demonstrates flows and cycles through spatial experience rather than through signs alone (Mozingo, 1997). California Scenario (1980-82) makes the same case at larger scale by staging source, channel, and garden as distinct episodes, but here at Chase condenses this into a compact bowl for view only (Treib, 2006).

Material carries the story in the hand and underfoot, even when perceived solely from above. The Uji River stones rest on a subtly undulating substrate so that boulders seem to float, implying current and deposition without mimicry. With a limited palette, small shifts in light, shadow, and water register immediately, and the ground reads as geologic rather than decorative (Yoshioka, 2006). The open-air design of the garden encourages natural geologic process: stone lives outdoors and takes on weather and time, so these materials register process as they age (Edgerton Martin, 2009; Barlow Rogers, 2005). From sculptural training came the Modernist respect for the nature of materials, wielded here as geologic mass and ground modulation express ecological work that keeps the invitation broad (Apostolos et al., 1994).

Set below grade, the circle forms a quieter air mass than surrounding streets. When wet, the water evaporates to cool and resonates to mask; when dry, the lowered floor reveals itself and a zen-like atmosphere at the edge. These are not incidental comforts but the instruments with which the plaza performs, since thermal ease and a softened sound field extend stays and make shared occupation agreeable (Yoshioka, 2006; Mozingo, 1997). The same sectional intelligence appears at the Beinecke court and in other bounded ensembles, constituting a portfolio of climate and ecological pedagogy throughout Noguchi’s work (Yoshioka, 2006).

Precedents clarify the method and its audience. At Morenuma (1988-2004), Noguchi preserved ridges and allowed post-storm flows to keep the courses they found, reading the site rather than enforcing an image; at the Domon Ken Museum (1984), sheet flow across stone and a composed horizon make time and change present in ordinary visits (Yoshioka, 2006). In Mexico he aimed for forms that speak plainly to working publics, reinforcing intelligibility as a civic value (Oles, 2001). Systems thinking nurtured in long conversation with Buckminster Fuller favors clear relationships among parts rather than isolated objects, aligning with ecological process design and with Chase’s condensed lesson in water, stone, air, and use (Sadao, 2011). Ecology becomes the operative medium: seasonal hydrology the script, stone the recorder of time, and section the climate device, all legible from the edge (Yoshioka, 2006; Mozingo, 1997; Treib, 2006; Barlow Rogers, 2005).

-

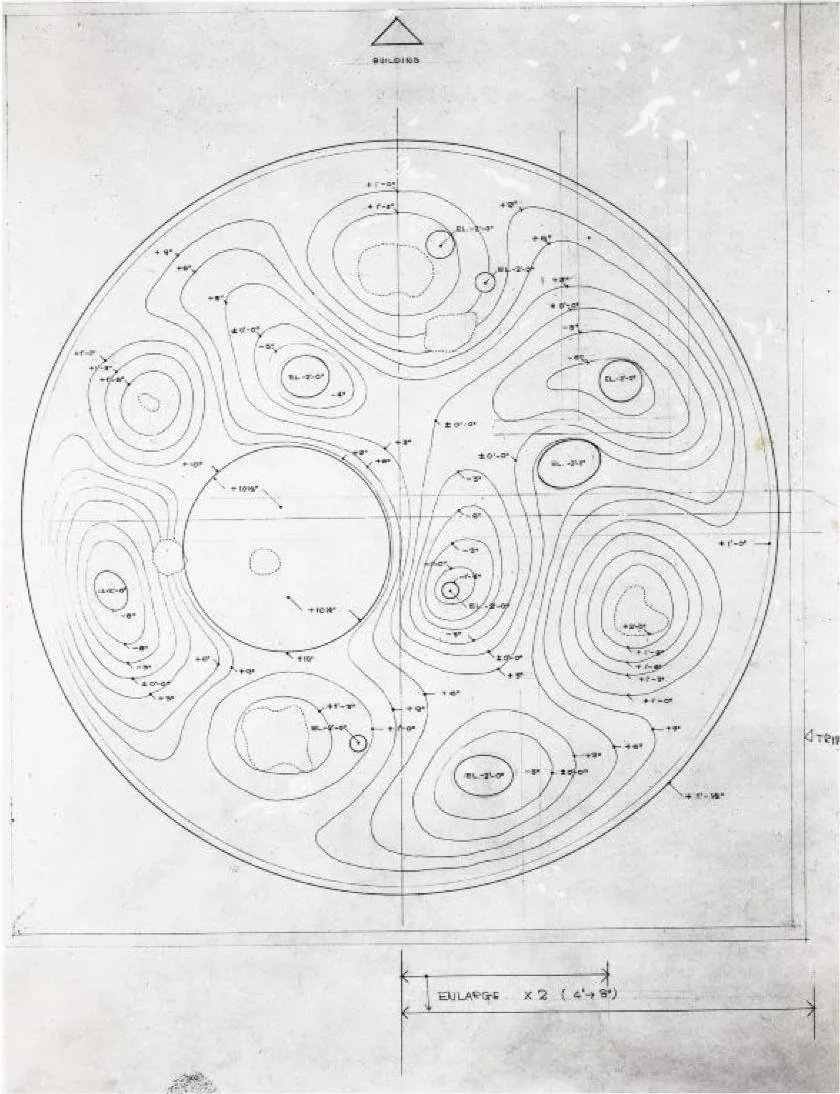

The plan for Sunken Garden (1961-64) at Chase Bank (Noguchi, 1961)

Conclusion

Noguchi’s civic ambition is quiet and precise, felt in the body as much as seen by the eye. At Chase the tools are spare: a circle that eliminates hierarchy, a lowered floor offered as a view rather than a stage to enter, and a seasonal script that turns water on and off. Together they form a city room at the edge where people pause, look, and share space without instruction, and where air, sound, and light are tuned for ordinary comfort (Yoshioka, 2006). The same grammar recurs elsewhere, even if spatially different: UNESCO composes approach and encounter through walking (Treib, 2003), the Beinecke garden confirms stacked vantage as gentle reciprocity between terrace and court, and the California Scenario renders water and ground as legible episodes for everyday users (Treib, 2006). Even still, the palette of egalitarianism and ecology remain present.

The form and ecology complement each other for human occupation: clear plan and section set invitations people accept, so status cues drop away and shared occupation along the parapet feels warranted on private land serving public life (Lasater Hill et al., 1988; Yoshioka, 2006). Tuned microclimate meets the body where it is: cooler air, calmer sound, and soft fascination are linked to lower stress and restored attention in the span of a glance or a short stand at the rail (Ulrich, 1984; Kaplan, 1995). Ecological process made apparent aligns comfort with performance: when hydrology, weathering, and seasonal change are grasped through experience from above, stewardship follows and ecology ceases to be backdrop (Mozingo, 1997; Yoshioka, 2006). In the Modernist ideals of civic engagement, the open figure and shared vantage serve as a daily practice of mutual notice in the financial district (Lyford, 2003). With such means, a plaza on corporate land becomes a public room at the edge where social welfare, public health, and ecological performance reinforce one another in daily use, as Noguchi intended (Yoshioka, 2006; Ulrich, 1984; Kaplan, 1995; Treib, 2006). In the quiet grammar of circle, stone, and water, the city learns how to be together.

-

Isamu Noguchi overlooking the Riverside Playground (1961-62) model, c. 1961 (Witcher, 2013)

Works Cited

Apostolos-Cappadona, D. & Altshuler, B. (Eds.). (1994). Isamu Noguchi: Essays and conversations. Harry N. Abrams.

Barlow Rogers, E. (2005). Three modern designers and their gardens. SiteLINES: A Journal of Place, 1(1), 2-8. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24889213

Duus, M. (2004). The life of Isamu Noguchi: Journey without borders (P. Duus, Trans.). Princeton University Press. (2000)

Edgerton Martin, F. (2009, November). Abstractions of nature. Landscape Architecture Magazine, 99(11), 88-91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44791942

Hoffman-Kuroda, L. (2020). Isamu Noguchi’s wartime playscapes. Verge: Studies in Global Asias, 6(2), 42-46. https://doi.org/10.5749/vergstudglobasia.6.2.0042

Hubard, O. M. (2008). The act of looking: Wofgang Iser’s literary theory and meaning making in the visual arts. Journal of Art & Design Education, 27(2), 168-180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2008.00572.x

Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169-182. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Lasater Hill, J., Tucker, S. C., Galbraith, L., Spomer, M. J., Wise, S., & Birdsall Lander, J. (1988). Instructional resources: Issues in public sculpture. Art Education, 41(6), 25-32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3193087

Lyford, A. (2003). Noguchi, sculptural abstraction, and the politics of Japanese American internment. Art Bulletin, 85(1), 137-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043079.2003.10787064

Mozingo, L. A. (1997). The aesthetics of ecological design: Seeing science as culture. Landscape Journal, 16(1), 46-59. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43324306

Oles, J. (2001). Noguchi in Mexico: International themes for a working-class market. American Art, 15(2), 10-33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3109345

Petkanas, C. (2004, October). Noguchi’s other art: A fresh appreciation for the sculptor’s iconic furniture. Architectural Digest, 61(10), 130-134.

Sadao, S. (2011). Buckminster Fuller and Isamu Noguchi: Best of friends. 5 Continents Editions.

Treib, M. (2003). Noguchi in Paris: The UNESCO garden. William Stout.

Treib, M. (2006). Sculpture[d] park. Landscape Architecture Magazine, 96(5), 106-117. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44676109

Ulrich, R. S. (1984). View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science, 224(4647), 420-421. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6143402

Witcher, D. T., DeArmond, A., & Williams, A. (2013). Isamu Noguchi’s utopian landscapes: A study in time and space. Unitas Press.

Yoshioka, E. (2006). The garden as a sculptural space: The evolution of Isamu Noguchi’s garden projects and their relationship to traditional Japanese gardens (1441060) [Master’s thesis, California State University Dominguez Hills]. ProQuest.

Image Addendum

Falk, S. (1964). Sunken Garden of Chase Manhattan bank [Photograph]. ARTSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14707970

Lavine, A. (1964). Sunken Garden of Chase Manhattan bank [Photograph]. The Isamu Noguchi Catalogue Raisonné. https://archive.noguchi.org/detail/artwork/759

Noguchi, I. (1961). Plan for Sunken Garden [Photograph]. The Isamu Noguchi Catalogue Raisonné. https://archive.noguchi.org/detail/artwork/759

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. (c. 1958). Unesco gardens [Photograph]. ARTSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13581676

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. (1970). Expo 170 fountains Osaka, Japan [Photograph]. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.13572898

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. (1982). Riverside playground [Photograph]. The Isamu Noguchi Foundation. https://archive.noguchi.org/Detail/artwork/8274

The Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum. (2007). Noguchi table [Photograph]. ARTSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.14651679

Stoller, E. (1968). View with the sculpture “Red Cube” by Isamu Noguchi, 1968 [Photograph]. ARTSTOR. https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.18115233