The Very First Baseball Stamp

A Stamp? Why You Might Actually Be Interested

Much like the game of baseball itself, the first pictorial postage stamp which depicts the playing of our bat-and-ball sport cannot be entirely claimed by the Americans. While many cultures have left their distinct marks on our beloved game, only two nations - one of them the United States - can lay claim to the very first baseball stamp. The story of this particular baseball stamp is surprisingly volatile, and is about colonialism and imperialism as much as it is about sportsmanship and athleticism; it is about chaos and facing the unexpected as much as it is about organizing and planning. Finally, this is a story about how the game which we love can bring us closer together, and how sometimes it can tear us apart.

Upon the conclusion of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Spain had ceded control of its various colonies to the United States, including the Philippine Islands. In their quest to instill self-governance on the Islands, the U.S.-controlled Insular Government established myriad departments, necessitating a postal service, and thus American-Philippine postage. Into the early twentieth century, these practical, utilitarian stamps were simply reissues of stateside designs with a bold “PHILIPPINES” printed across their faces. The first Island-designed and printed stamps were issued in 1906, featuring a portrait of Jose Rizal, a hero and martyr in the fight for the liberation from Spain.

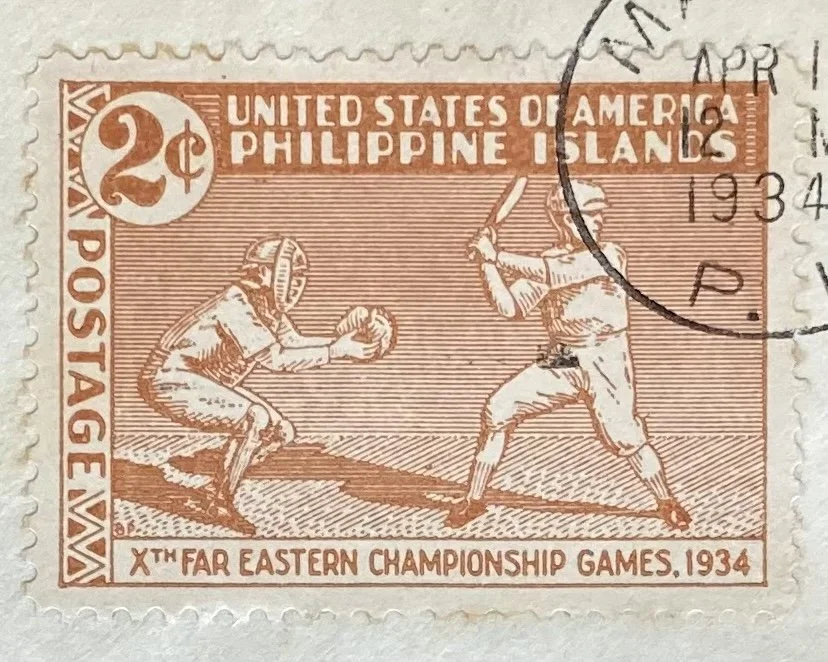

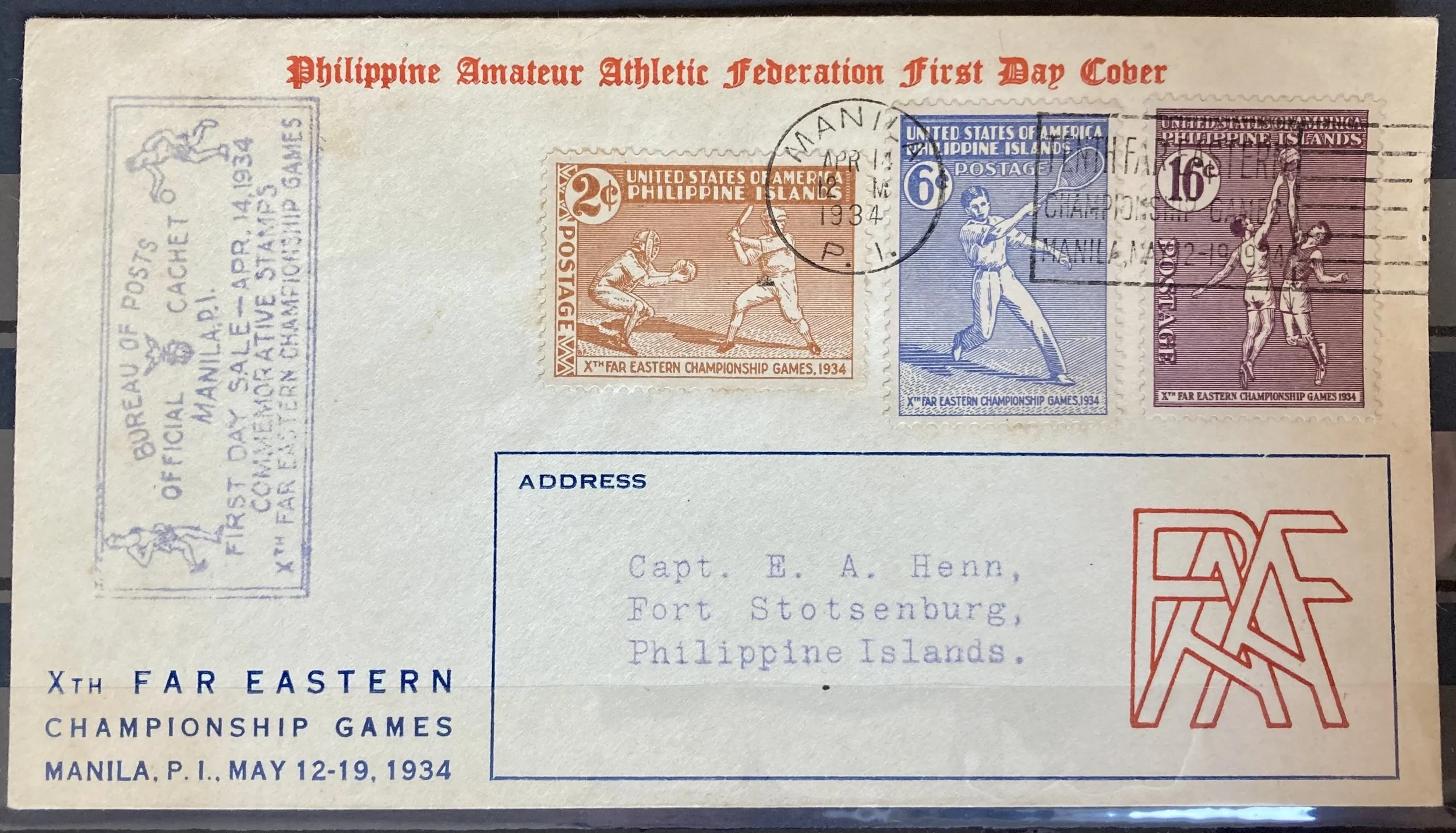

The particular stamp in question, officially registered as Scott #380, is an unimpressive orange-tan color, featuring a hatched image of a right-handed batter at the plate and a catcher behind him. Issued on April 14, 1934, along with two others in its set (incidentally also the first tennis and basketball stamps), it commemorates the tenth Far Eastern Championship Games held in Manila the following month. In their path to issue the very first baseball stamp, the postal service inadvertently immortalized the final iteration of the Games.

This postage stamp straddles two separate timelines, coinciding in this single issue. At one extreme, it is the very first: the first baseball stamp. The other extreme, its end, has much further reaching implications: none of the participating nations thought that this would be the last Games, and there were even plans for an eleventh in Japan. As we’ll soon discover, Japan’s imperialism was insurmountable. As much as this stamp represents the best of man coming together in athletics, it must also reflect the self-righteous assertion of ideology on unwilling peoples, the dissolution of diplomacy, the deterioration of the region into world war, and the eventual failure of baseball in the Philippines.

A Brief History of Baseball in the Philippines

Just as they had brought their bureaucracy, the Americans introduced the Islands to baseball. According to Joseph Reaves, in his 2002 book, Taking in a Game: A History of Baseball in Asia, there was “no real history of team sports” throughout the Philippine villages, and Spain had faced trouble enticing the leisurely Filipinos to partake in athletics. While children sometimes played sipa - a seemingly unchallenging soccer-like game - and adults bet on cockfights, throughout the Islands there were both a “long-standing aversion to physical exercise as a form of entertainment” and, particularly for elite Filipinos, a “deep-seeded desire… to stay out of the sun” (p. 91). Thus, the Manila Baseball League, established in 1902, was composed “almost entirely of U.S. military teams” (Fitts, 2012, p. 218).

But baseball seemed to pique the Filipinos’ interests. Upon being instated to the Governorship in the Philippines, William Cameron Forbes, once the head coach of Harvard University’s football team (Gems, 2016, p. 79) quickly moved to establish organized athletics amongst the youth on the Islands. President McKinley ensured that his policy of “benevolent assimilation” (Brown, 1913, p. 479) would be imposed throughout the Islands with the proper people at the helm, and by 1905, the Manila schools had started their own scholastic baseball league. According to Forbes, “the elders neglected the cockpit [betting] to come and see the games of the young ones and cheered them on” (Reaves, 2002, p. 99).

Filipinos were introduced to Major League action during the first American barnstorming tour across Asia in 1908, even fielding an all-Filipino team to compete against the Americans. After one particularly spectacular play, nearly “5,000 persons were on the field congratulating [the Filipino] player, and it was nearly an hour before the game could be again started” (Spalding, 1911, p. 380).

The islanders were not to be outdone, and by 1913, Alejandro Albert had fielded an all-Filipino team, the Brownies, to tour the United States. Heroically known as the “father of Philippine baseball,” Albert shared his insight with American reporters on the popularity of the sport in the Pacific: according to the coach, Island league games had often drawn “13,000 to 20,000” spectators, each charged between a quarter and a dollar for admission (Pittsburg Press, 1913, p. 12). By 1914, it was clear that “baseball had seemed to fill a long-felt want” (Crow, 1914, p. 120) for athletics in the Philippines.

It was clear that “baseball had seemed to fill a long-felt want” for athletics in the Philippines.

As Baltimore Oriole Arlie Pond finished his five-hit shutout against to-be Hall of Famer Nap Lajoie and the (original) Philadelphia Phillies, he knew it would be his last soire on the mound for a while. While the Orioles were having financial difficulties (of course) and cut him, they resigned him later that summer. No, that wasn’t it: the year was 1898, and the newly minted Army doctor was ordered to report to Fort Myer near Washington, D.C., as the war between the United States and Spain raged on. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Pond, along with the rest of the 10th Pennsylvania Regiment, were shipped out to the Philippine front, not to fight against Spain, but to swiftly squash the Philippine-liberation insurrectionists.

Outside of Luzon and its capital, Manila, American interventionism appeared diametrically opposed to their ideals of “benevolent assimilation.” A 2018 report by Gerald Gems found that not only had the imperial American army enslaved many Filipinos, but while the villagers were toiling, American soldiers desecrated Church grounds by playing baseball in its plaza. The islanders were so irate that they conspired with local guerrilla forces to attack and kill forty-eight out of seventy-four American colonizers. The story of the very first baseball stamp would be incomplete without the accurate representation of all of the United States’ actions.

While the Oriole pitcher was not present at the aforementioned incident, many like him were, and his regiment saw similar brutality. War is hell, and we should always strive for diplomacy. This is not the only time in this story that diplomacy would fail, and man would be ripped apart: there is no diplomacy in invasion.

If you can get out of hell, as Dr. Pond did, you at least deserve peace. The soldier never starts the war, after all. Serving, of course, as a field doctor, Dr. Pond was generally able to avoid combat, and put his time to use treating the ills and ailments of local villagers. The Manila Times reported of Arlie, “much of his medical life was given gratuitiously to” the Filipino people. In addition to his medical practice, he coached the all-black 25th Infantry Regiment baseball team, defeating the Manila League champions along the way. He may be halfway around the world from home, but he still has baseball.

In 1906, Dr. Pond was re-stationed in Cebu, an island some four hundred miles south of Manila, and the former Philippine capital under Spain. Along with Reverend George Dunlap, once a Princeton University catcher, the pair were able to establish a “hotbed of Filipino baseball” on Cebu, coaching their high school team to multiple consecutive championships. The all-star catcher for Pond’s team, Regino Ylanan, helped to win a friendly game against Waseda University from Japan when they visited in 1912 (Reaves, 2002, p. 95-96). Ylanan would himself become a doctor, and would quietly become much more integral to the story of this very first baseball stamp. We will meet Dr. Ylanan in a few years…

The Far Eastern Championship Games

The rapid adoption of baseball in the Philippines was well underway, but further athletic development would have been impossible without the direct influence of Governor Forbes. Critical was his decision to enlist University of Illinois basketball coach Elwood S. Brown to head the newly established Manila Y.M.C.A. in 1911 (Tlusty, 2016, p. 39). Shortly after his arrival to the Islands, Brown had “adults and children playing basket ball, volley ball, and indoor base ball… by the hundreds” (Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide, 1919, p. 219). Incidentally, the man who would bring us the Far Eastern Championship Games would inadvertently end the brief reign of baseball as the most popular sport in the Philippines.

Ordered to the resort-like Naval base in Baguio on Luzon, about one hundred and fifty miles from Manila, Elwood was tasked with organizing that summer’s athletics. Likened to the Olympic Games by World’s Work reporter Thomas Gregory, no doubt the head of the Y. gained valuable experience that would aid him in creating the first Asian international athletic tournament. Upon his return to Manila, Brown worked closely with Governor Forbes to establish the Philippine Amateur Athletic Association to promote “play for everybody” and “to bring every country in the Orient into competition” (England, 1926, p. 19).

Brown’s initiative to bring together all Asian peoples in sport was not deterred by the inauguration of President Woodrow Wilson in 1913 and his increased pace in the “process of self-government” (Gems, 2016, p. 84-85) in the Philippines. Governor Forbes by that time had already implemented the proto-Olympic Manila Carnival, a “commercial and industrial fair” (CITATION NEEDED) which not only promoted integrated interracial gamesmanship, but also featured multiple women’s athletic events (Gems, 2016, p. 80). In fact, the ousting of Governor Forbes seemed to further serve Brown’s mission, as he was then free to head the P.A.A.A. (later changed to the Philippine Amateur Athletic Federation, or P.A.A.F.).

Working in concert with the Manila Y.M.C.A., aided by“instrumental” efforts from the secretaries from the Chinese and Japanese branches, Brown and Forbes established the multi-national Far Eastern Olympic Association, before the International Olympic Committee forced Brown to change the name to the Far Eastern Athletic Association (F.E.A.A.). Brown very much wanted his organization and event to be in “a position of close cooperation” with the I.O.C. (Brown, 1913, p. 481). Elwood Brown, despite his nomenclature misstep, was quickly becoming one of the most influential athletic benefactors in not only the Philippines, but the rest of Asia, and, in fact, the world.

True to its stated purpose of sharing athletics across the Far East, Brown, Forbes, and their F.E.A.A. extended invitations to various territories and nations throughout the region. For the first iteration of the Far Eastern Championship Games, held in Manila in February, 1913 (England, 1926, p. 18), six nations sent teams and delegations to compete, though only the Philippines, China, and Japan sat on the organizing council. The other three competing nations were: the Federated Malay States (now Malaysia), Siam (now Thailand), and British Hong Kong.

For the first Games, Japan was only concerned with their “love of baseball,” delegating only the ballclub from Meiji University and two runners to compete (Tlusty, 2016, p. 40). The Philippines would win gold in eight out of the eleven athletic events at the inaugural Games, but would lose the baseball title to Japan’s collegiate team.

The all-star catcher from Cebu, Regino Ylanan, would lead his team from behind the plate in the first Games, but he could not muster another win against Japan as he had under Dr. Pond. While he and his teammates earned only silver, Ylanan was “peerless” in the pentathlon, earning gold in not only that, but shot put and discus as well. Ylanan would go on to study medicine at the University of the Philippines, and would later receive a Bachelor’s of Physical Education at Springfield College in Massachusetts. After his stint as the track and field coach in Philippines’ Olympic debut in Paris, 1924, the doctor will return to our story at the beginning of the end…

This first competitive matchup would lead to a “healthy rivalry” between the two baseball-loving nations. The Philippines would take five out of the six subsequent titles, only losing to the team from Waseda University in 1917 (Reaves, 2002, p. 102). Japan bested the Philippines later in the 1927 and 1930 Games, bringing the running total to five wins for the Philippines, and four for Japan.

The Games proved to be marvelously popular in Manila and throughout Asia. For the first Games in 1913, over 15,000 people attended various events. The F.E.A.A. and F.E.C.G. were lauded by the International Olympic Committee, who in turn officially recognized the organization and event in 1920. While reporting for the I.O.C.’s Official Bulletin in 1926, Frederick England called the Games “second in importance only to the” Olympics (p. 18). It would have been impossible to know that they were quickly approaching complete disintegration.

As the Games progressed, the F.E.A.A. continued to extend invitations to non-council members. British India participated for its only Games in 1930, while Javanese from the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) and Saigon athletes from French Annam (now Vietnam) were invited to the 1934 Games. However, Annam withdrew before the start of the event. In the end, the issue of expanding the Games - albeit not to any of these aforementioned nations - fueled by the colonialist expansion of an empire, proved to be irredeemable.

1934: The First Baseball Stamp & the World on the Brink

MORE ABOUT RELEASE OF SET HERE

As much work that went into establishing the first Far Eastern Championship Games, arguably it was much more precarious and stressful to organize the tenth iteration to be held in May, 1934. By that time, W. Cameron Forbes and Elwood S. Brown were long gone. Brown had died of a heart attack in 1924, and Forbes (who lived until 1959) had been succeeded in 1916 by the first Filipino P.A.A.F. President, Manuel Luis Quezon, who would also later be elected the President of Commonwealth of the Philippines. It would be Quezon who ultimately oversaw the deterioration of Brown and Forbes’ initiative.

At the crux of this postal controversy, and thus, the eventual failure of the Games, lay Japan’s imperialism. Bisecting the concluded ninth Games (1930) and the upcoming tenth (1934) was an act blatantly antithetical to the sportsmanship that had been building in the region since well before the First World War, and so brazen that it resulted in Japan abdicating from the short-lived League of Nations.

Two years prior to the start of the tenth Games, in 1932, Japan had invaded the disputed Manchuria region on the Chinese mainland under the guise of liberating ethnic Japanese and Japanese sympathizers in the region (CITATION NEEDED). There, they installed a loyal regime in their new colony, Manchukuo. While this rightfully angered the Chinese government, colonialism is nothing new, so they and their athletic organization were more or less ready to proceed normally for the coming Games. Japan and the Philippines were likewise eager to showcase their athletic talents.

It was, however, the issue of invitations that led to the destruction of diplomacy, and the year-long planning turned to harsh, last minute, winter negotiations. As Kosuke Tomita describes in his 2019 report, “Developments in the Movement to Boycott the 10th Far Eastern Championship Games in Japan,” Japan’s athletic body insisted that an invitation to the Games be extended to their Manchukuo colony. The loyal leaders of Manchukuo saw themselves as an “independent state,” arguably more independent than the nation-states of the Dutch East Indies, who had received invitations in years’ prior, or even the Philippines themselves, then still under U.S. control (p. A57).

Not only were there international politics to consider, there were bylaws to follow:

1934 Scott #380, baseball at the 10th Far Eastern Championship Games, Manila, Philippines