JAPAN & PHILADELPHIA

1876 Centennial

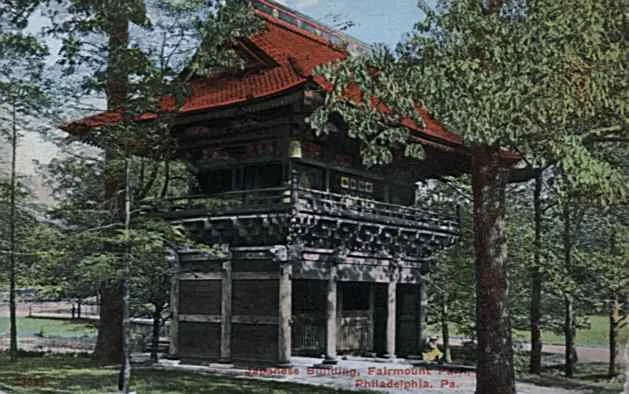

Photo: "Japanese Building, 1876". Photo of the entrance of the Commissioner's Building at the Centennial Exhibition. Here, you can see the intricate detailing and fine craftsmanship that astounded viewers. No. c180300 at the Free Library of Philadelphia.

Philadelphia, the birthplace of American democracy, was selected for the United States’ first ever World’s Fair, celebrating the 100th anniversary of her independence. Japan, eager to show off its new industrial might, sent seven thousand crates of fine silks, elaborate ceramics, and elegant bronze statues.

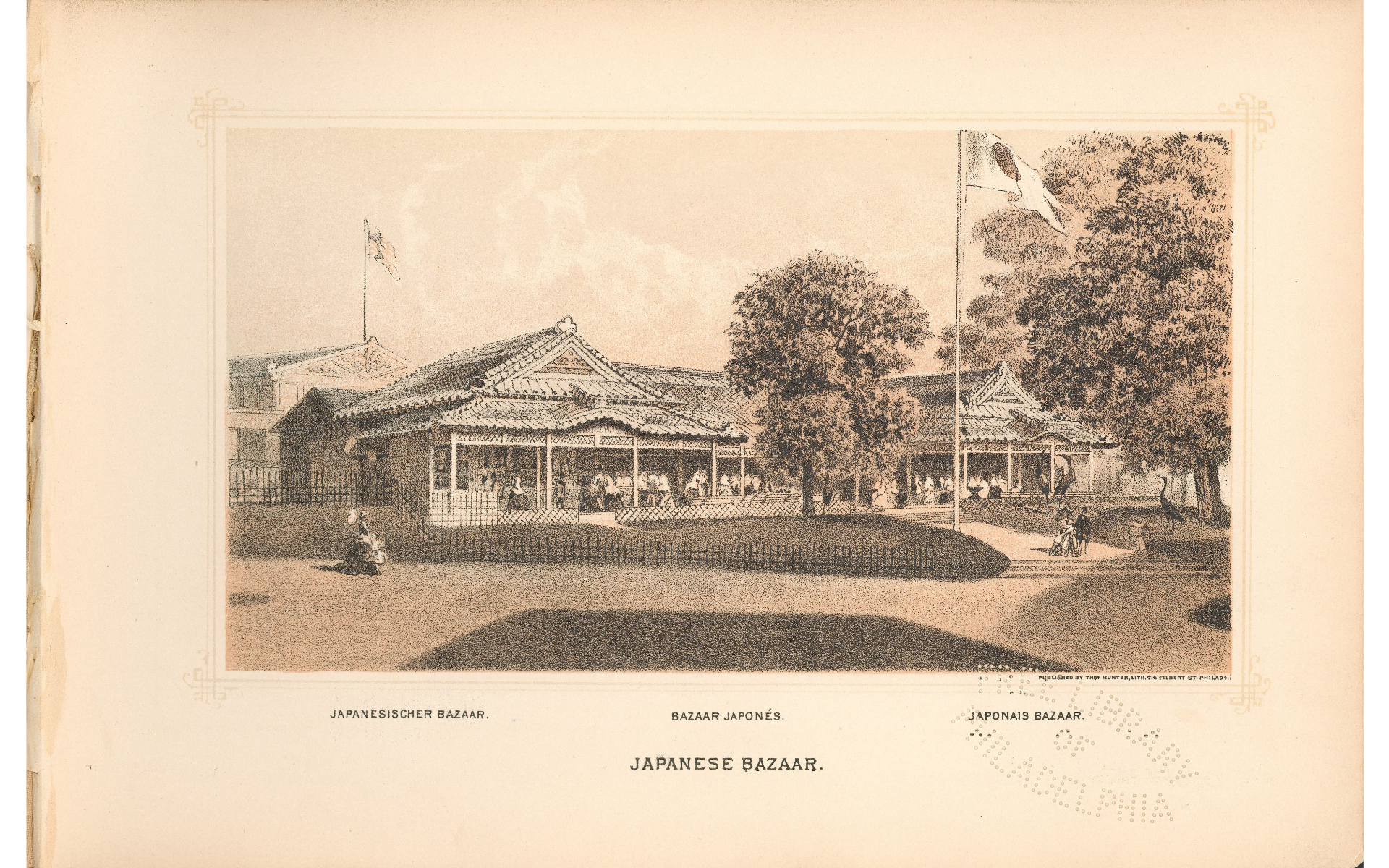

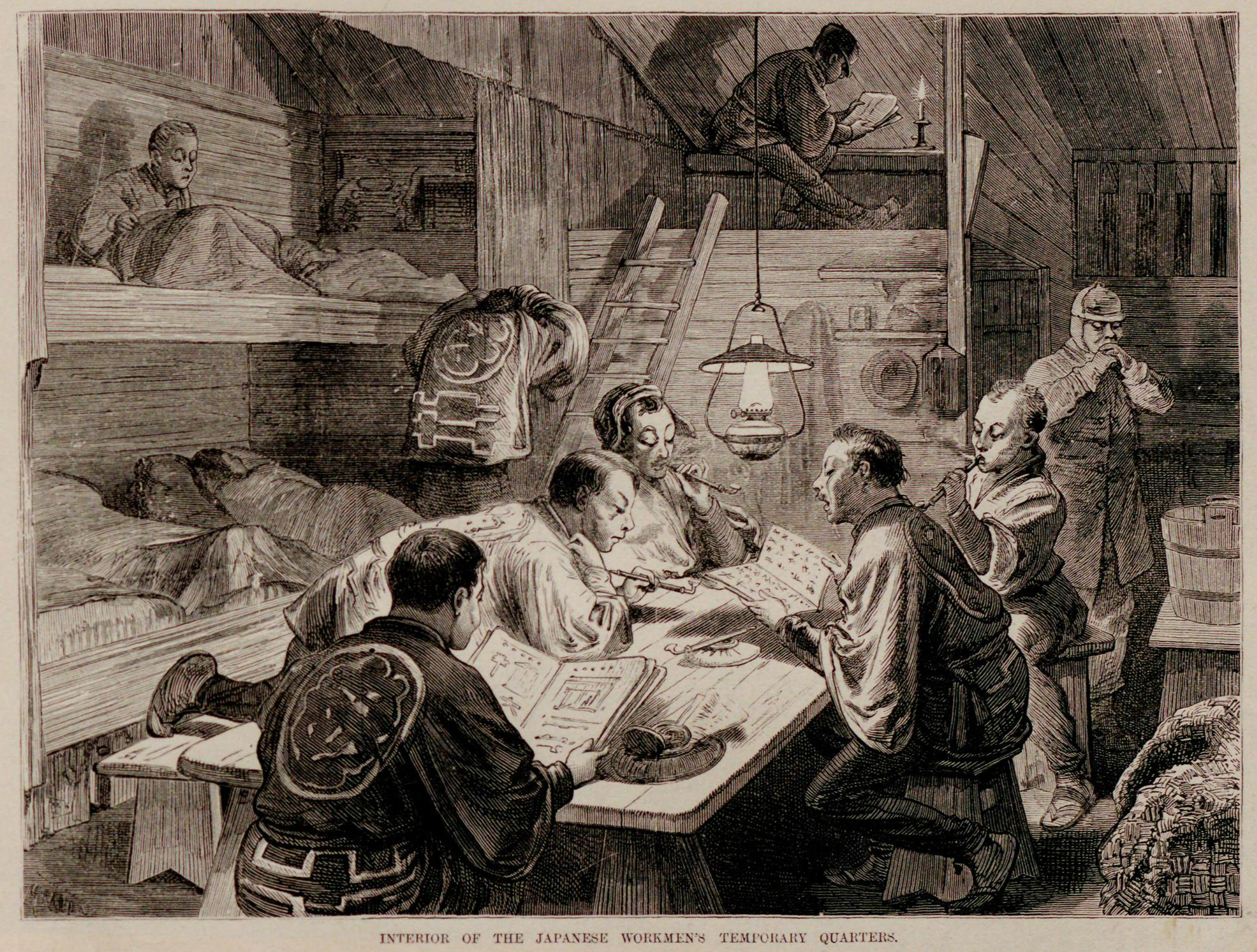

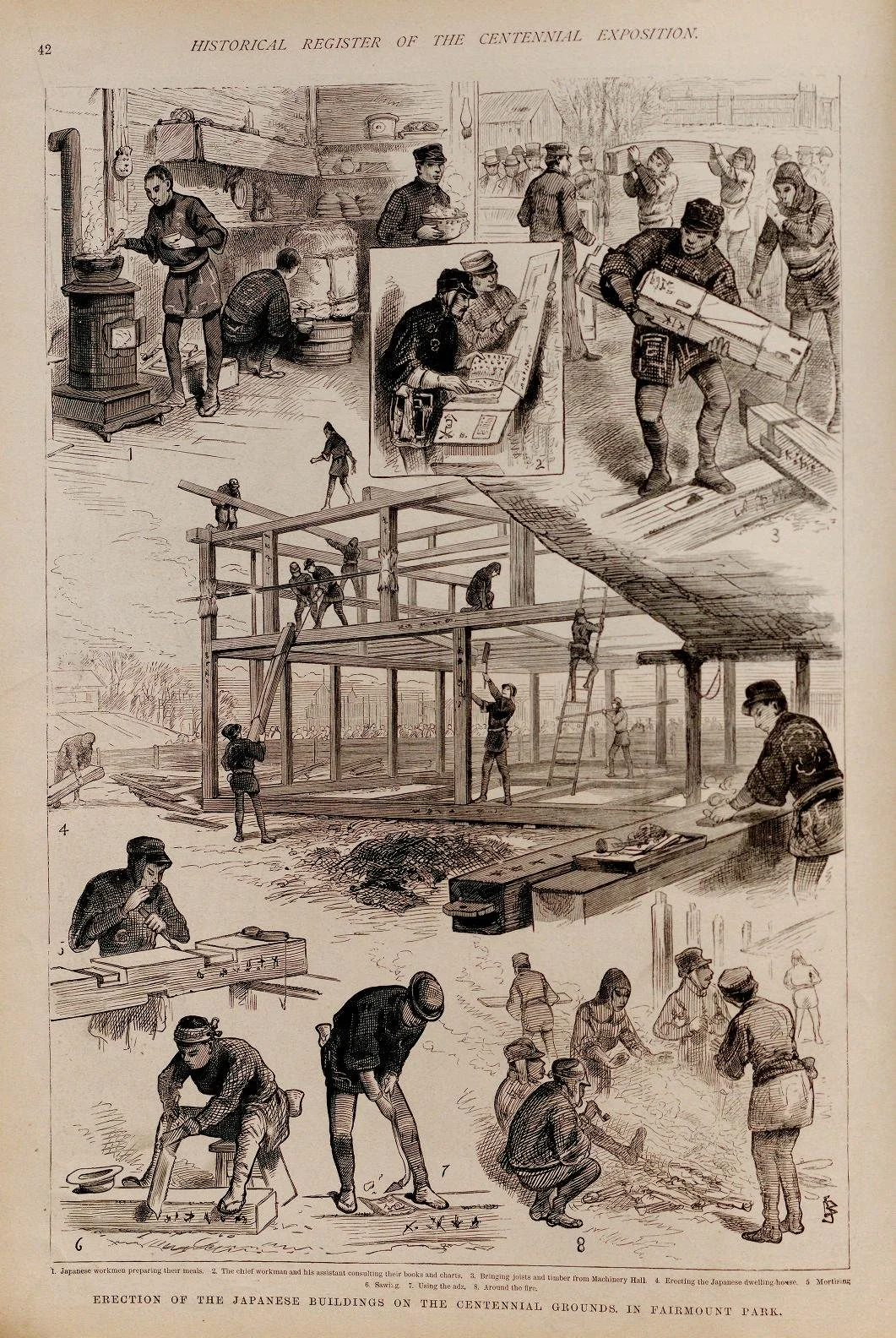

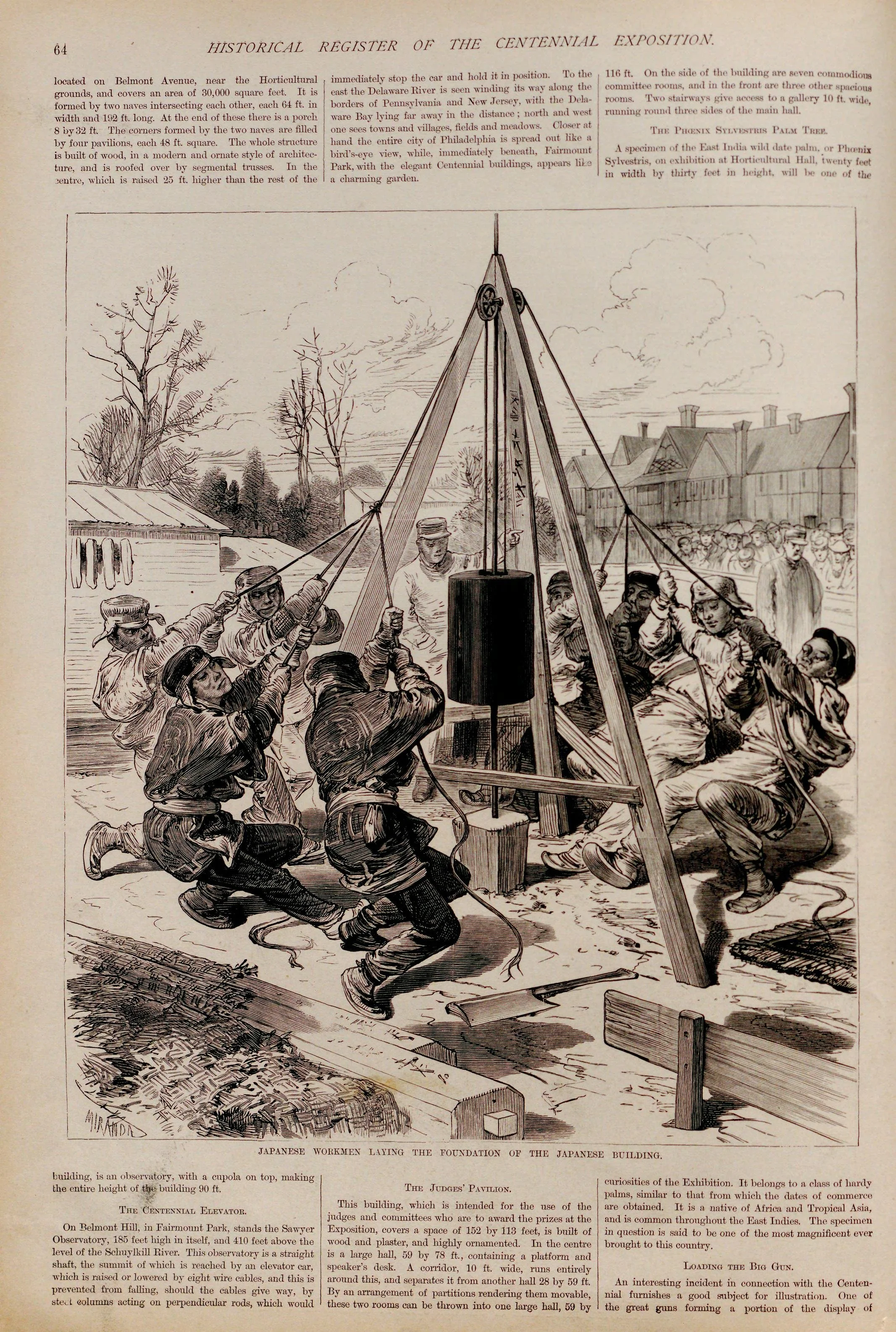

In addition, expert carpenters erected two magnificent buildings, the Commissioner’s Building and the Japanese Bazaar, designed by S. Kanazawa of Kaga. On the site, workers planted the very first Japanese garden in North America. The traditional construction process astounded visitors, attracting crowds to watch the carpenters at work.

The finished structures enchanted viewers, who were taken by the unique joinery, decorative lattice work, and masterful craftsmanship. In comparison, according to the official fair guidebook, all of the other buildings looked “commonplace and vulgar.” Though Japan sought to impress with its newfound industrialization, it was the traditional techniques that thoroughly captured the American imagination.

Nio-Mon Temple Gate

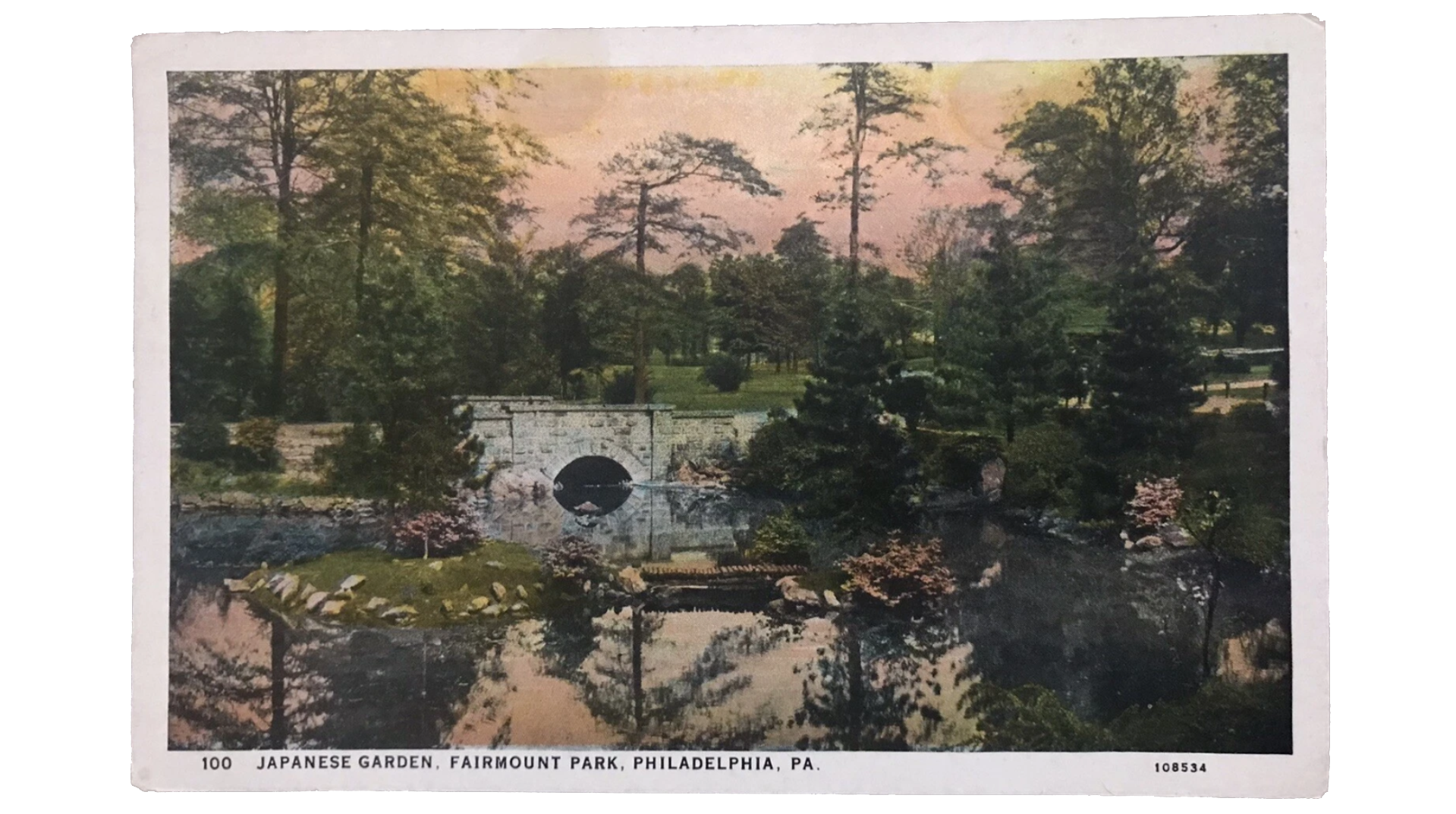

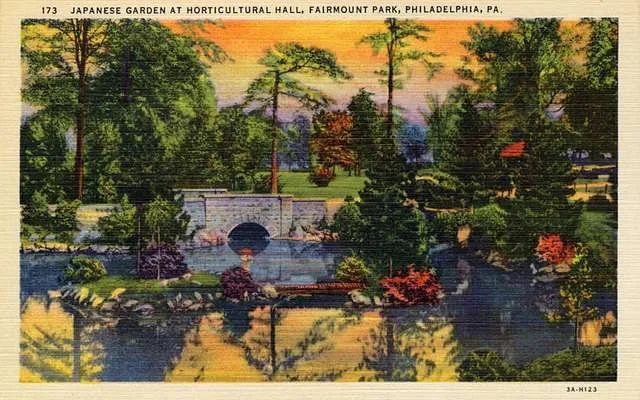

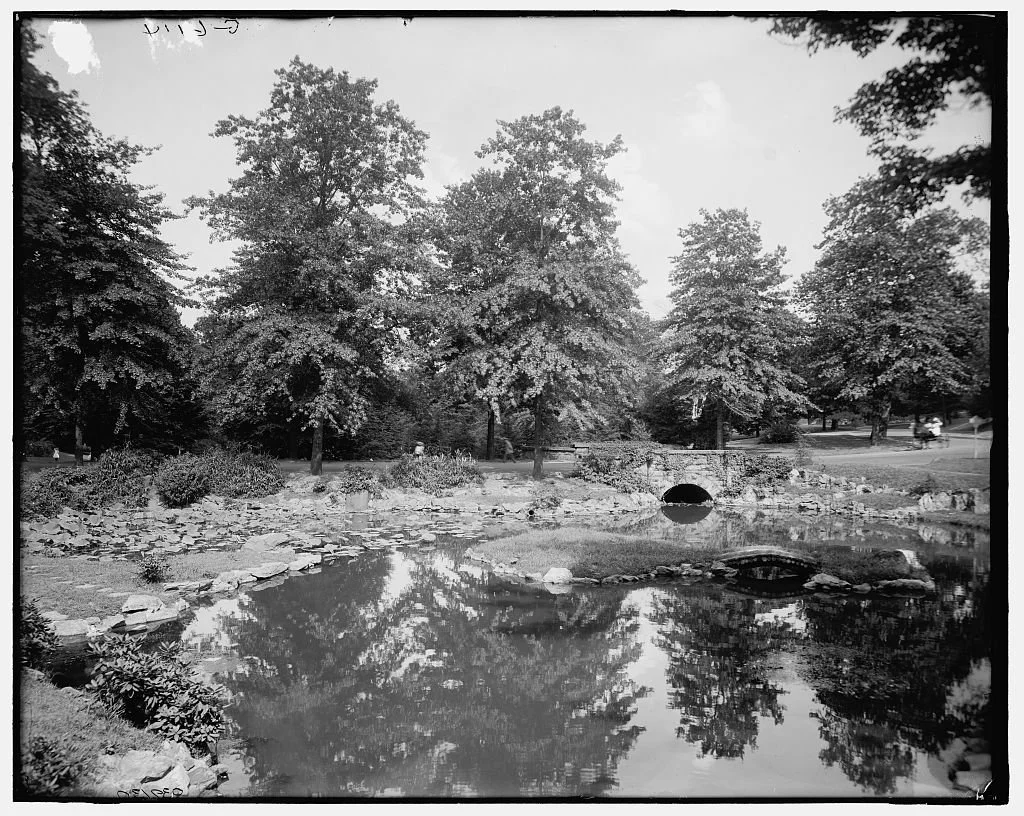

Once the 1876 Centennial concluded, the unsold wares were returned home and the buildings were deconstructed. Just a small pond survived, thought at the time to be the only lasting remnant of the Japanese exhibit. But it was about 200 yards away, located where you stand now.

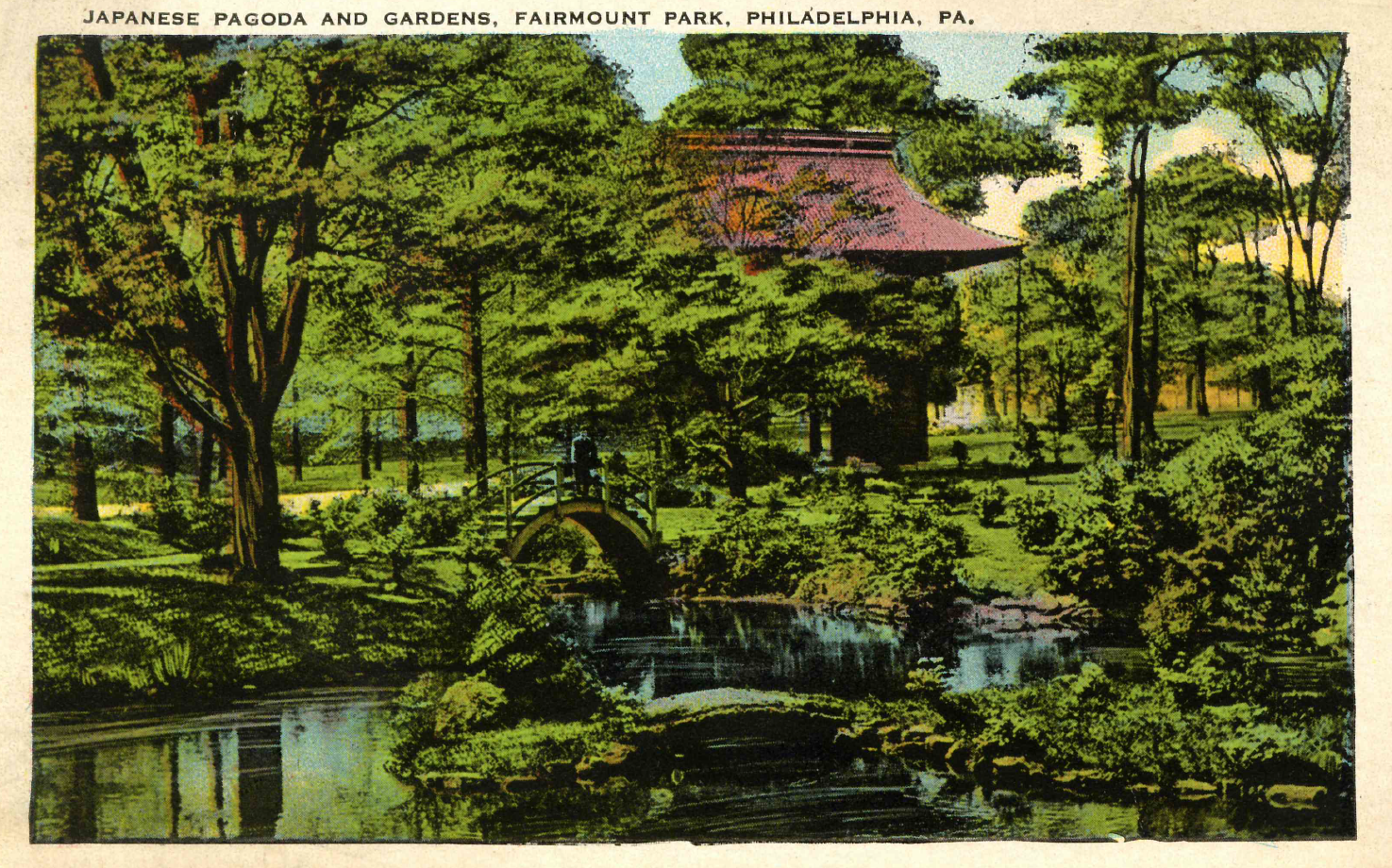

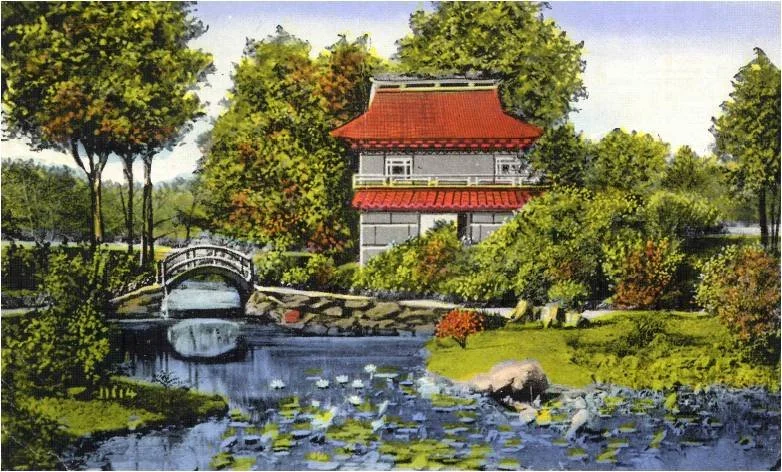

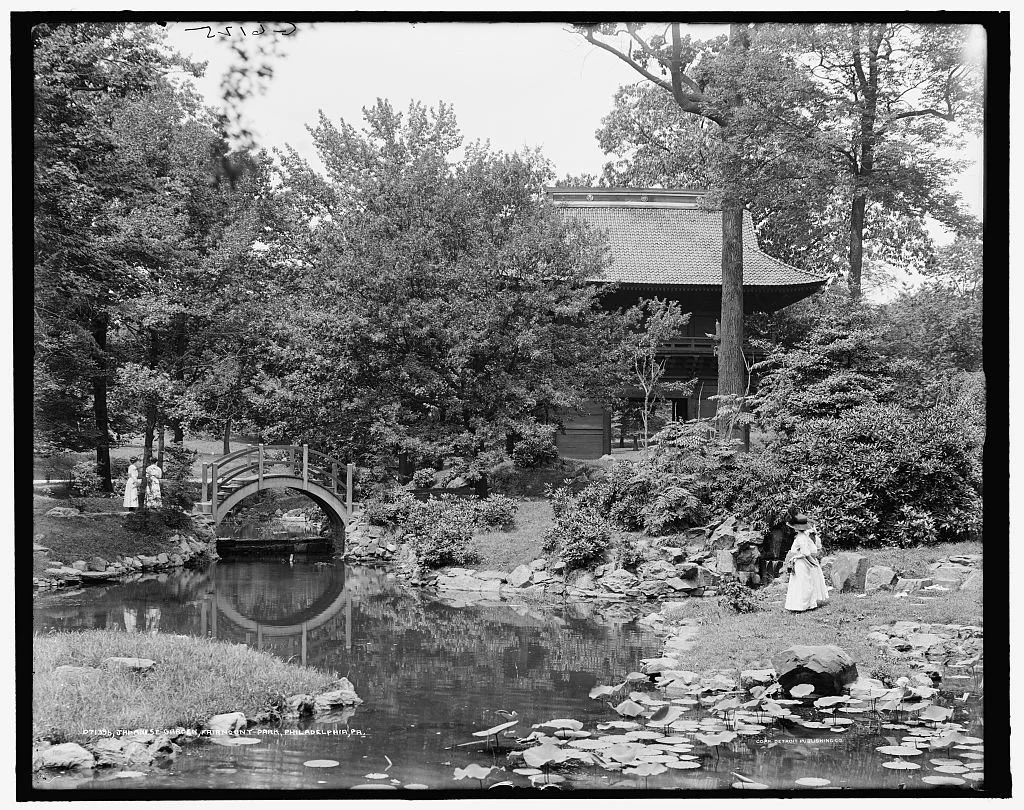

Halfway across the country, in 1904, the US held another World’s Fair to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Louisiana Purchase. Japan again presented their finery, but instead of creating new constructions, shipped a 14th Century temple gate from Furumachi in Hidachi Province.

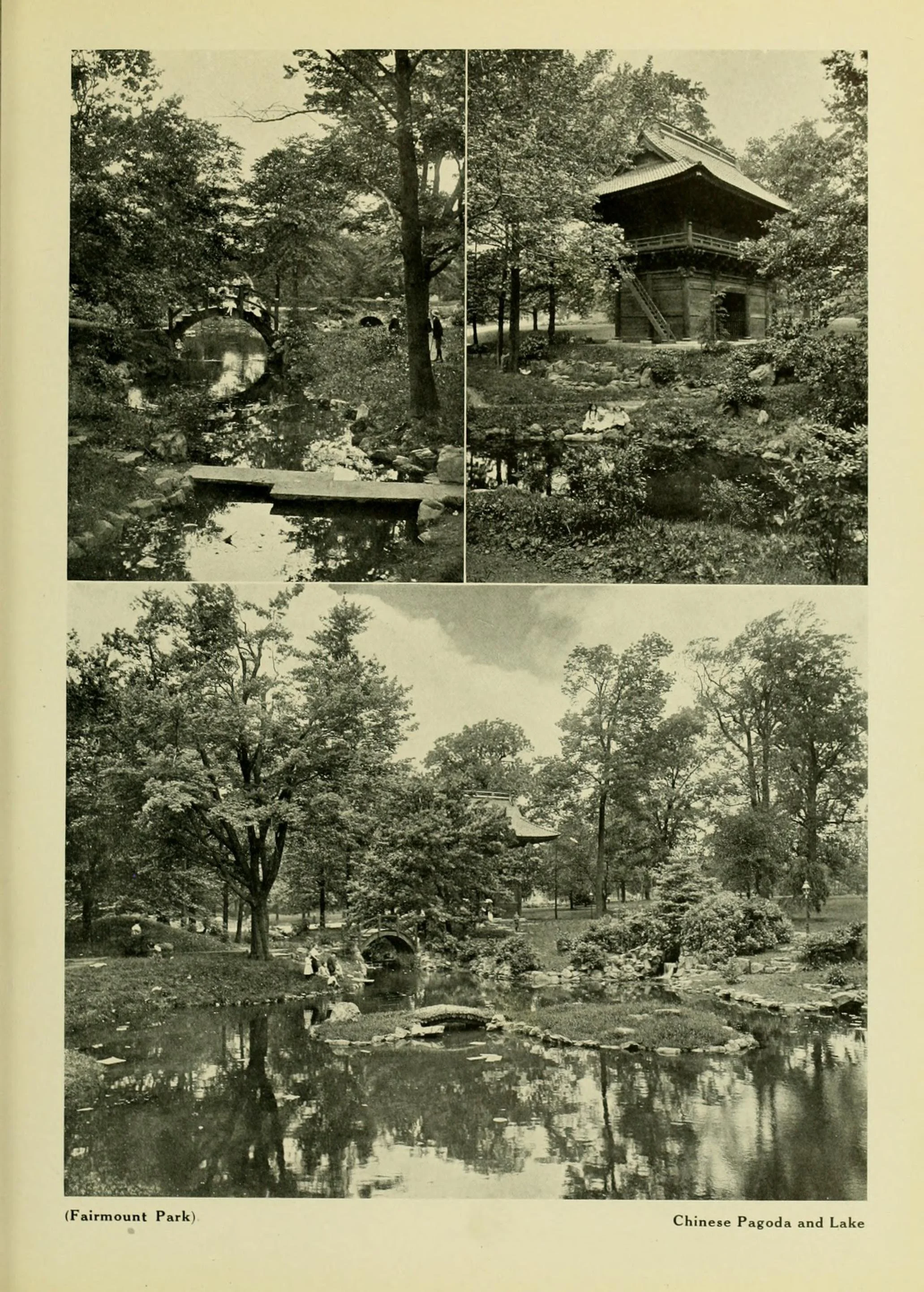

Intricately decorated and guarded by two Nio god statues, two Philadelphian industrialists purchased the entire structure and donated it to Fairmount Park, to be located at the suspected Centennial site. The two enlisted Yonehachi Muto, who just finished the Japanese garden at Morris Arboretum, to create a new stroll garden around the pond. For fifty years, the “Japanese Pagoda” was one of Philadelphia’s best-known and best-loved landmarks.

Photo: "Temple of Shinto - Fair Japan - Pike." The Nio-Mon at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, MO, in 1904. Previous archivists located this photo, with no trail. Any information is welcome.

Nio-Mon Burns Down

Though the Nio-Mon was admired, it was also vulnerable. With no budget for a gate or fence, the Nio-Mon suffered decades of neglect and vandalism. At one low point, even the Fairmount Park Commissioner thought that the beloved structure may need to be torn down. Much of the 500-year old ornament was relocated to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for safekeeping.

The Japanese Pagoda, however, would suffer a far more devastating fate. While under routine maintenance in 1955, a carelessly discarded cigarette ignited the wooden structure, enveloping it in a fiery blaze that lasted three agonizing days.

This is a rather fitting end to the glorious structure, as the Nio and the Mon symbolize the life and death of all things. Its demise was anything but untimely, as at that very moment, another Japanese structure was on display in New York, and would soon need a new home. Through its death, the Nio-Mon allowed Shofuso to live.

Photo: "Thousands See Blaze Wreck Famed Pagoda in Fairmount Park”. From the front page of the May 7, 1955 edition of The Philadelphia Inquirer, vol. 252, no. 127, p. 1