SHOFUSO IN PHILADELPHIA

Move to Philly

Photo:

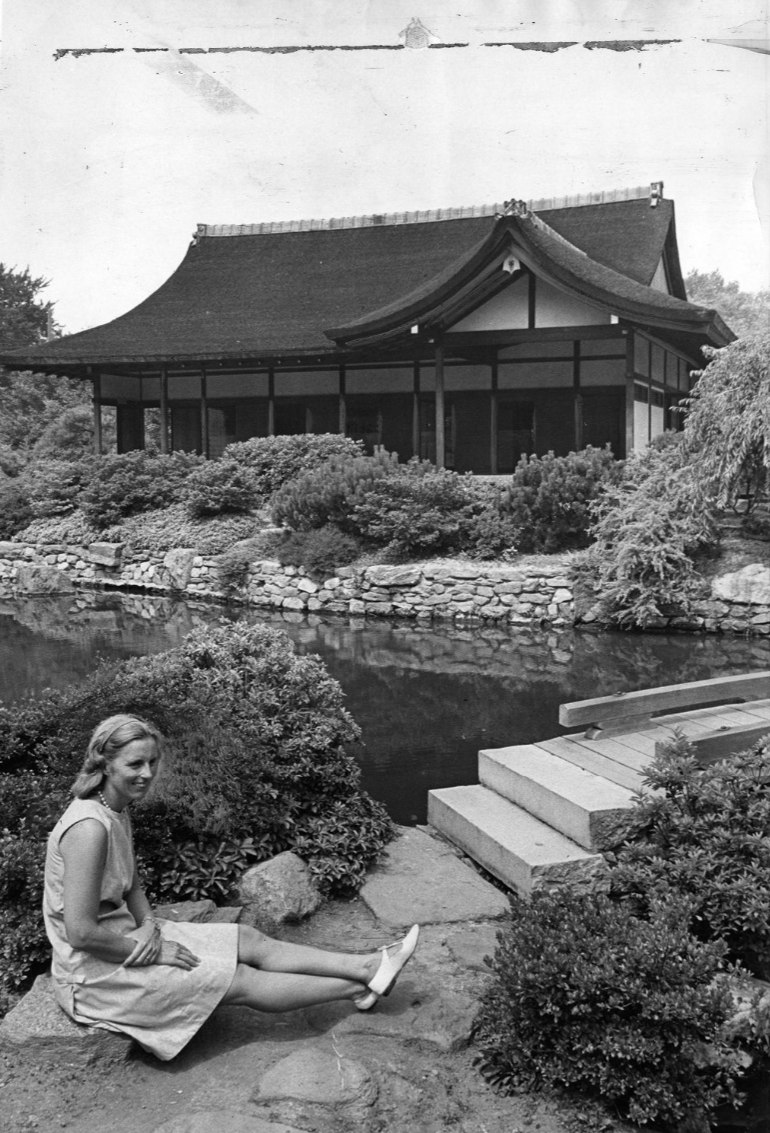

The Japanese Exhibition House concluded its New York showcase in October 1955. As a gift to the United States, Japan requested that the house find a new home on the East Coast. Through the advocacy of John Rockefeller and his friendship with Mayor Richardson Dilworth, Fairmount Park in Philadelphia was selected for Shofuso’s new home. With the recent tragedy of the Nio-Mon, the Park was eager to replace and continue its Japanese presence.

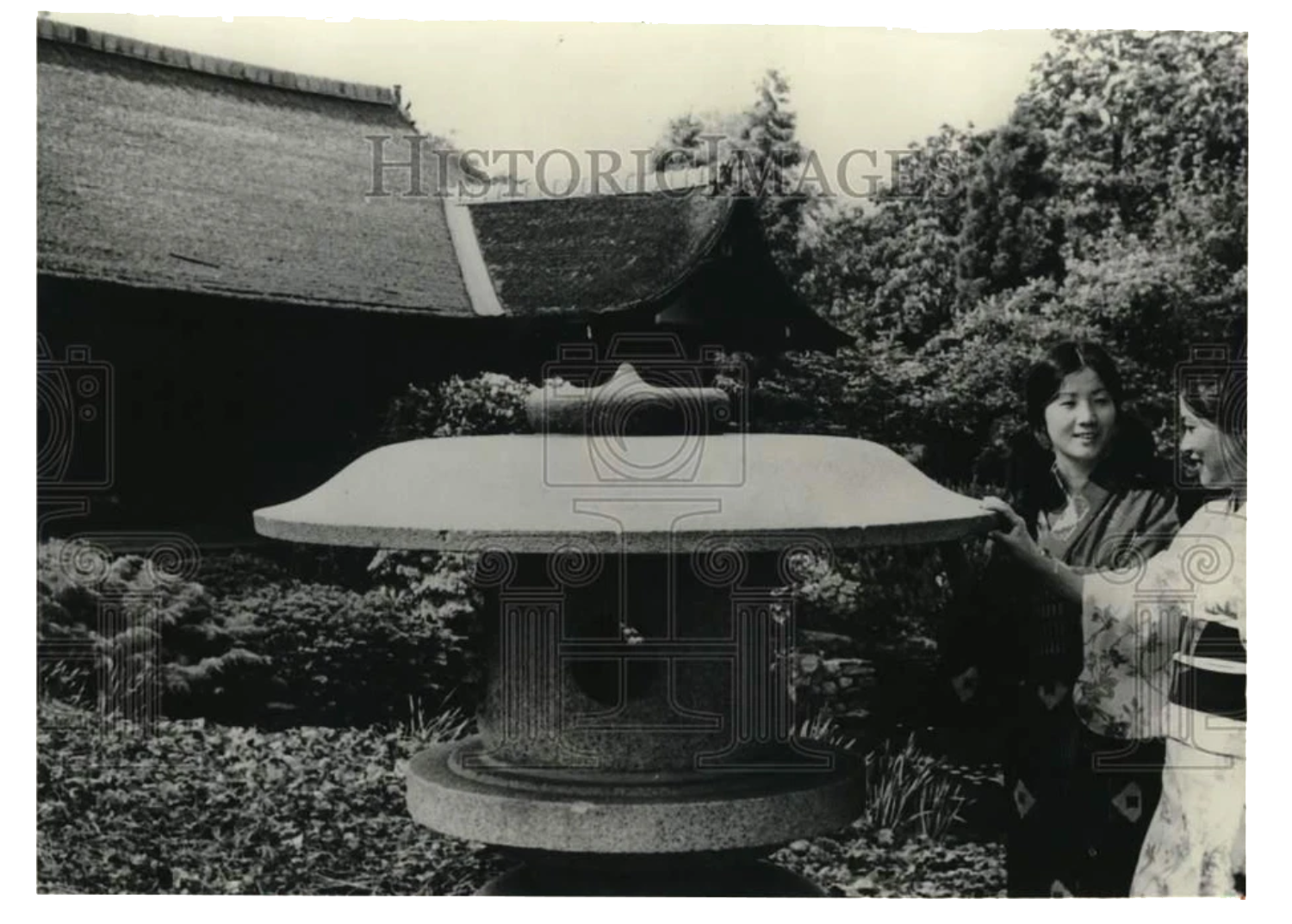

Shofuso opened to the Philadelphia public on October 18, 1958, almost exactly three years after it had closed in New York. Very quickly, the house and garden surpassed the Nio-Mon in popularity. The Fairmount Park Commission enlisted Japanese Philadelphian women clad in kimono to give outdoor only tours, emphasizing the exoticism of the house instead of its architectural intricacy and cultural significance.

The house, sitting on the site of the Nio-Mon, just a few hundred yards from the site of the Japanese buildings at the 1876 Centennial, became the latest in the line of Philadelphia-Japanese utsushi, a city seemingly very invested in maintaining a strong relationship with our friends from the East.

Video from construction in Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. From JASGP “Okaeri Okamura Footage 1954 1957” on YouTube

The Garden

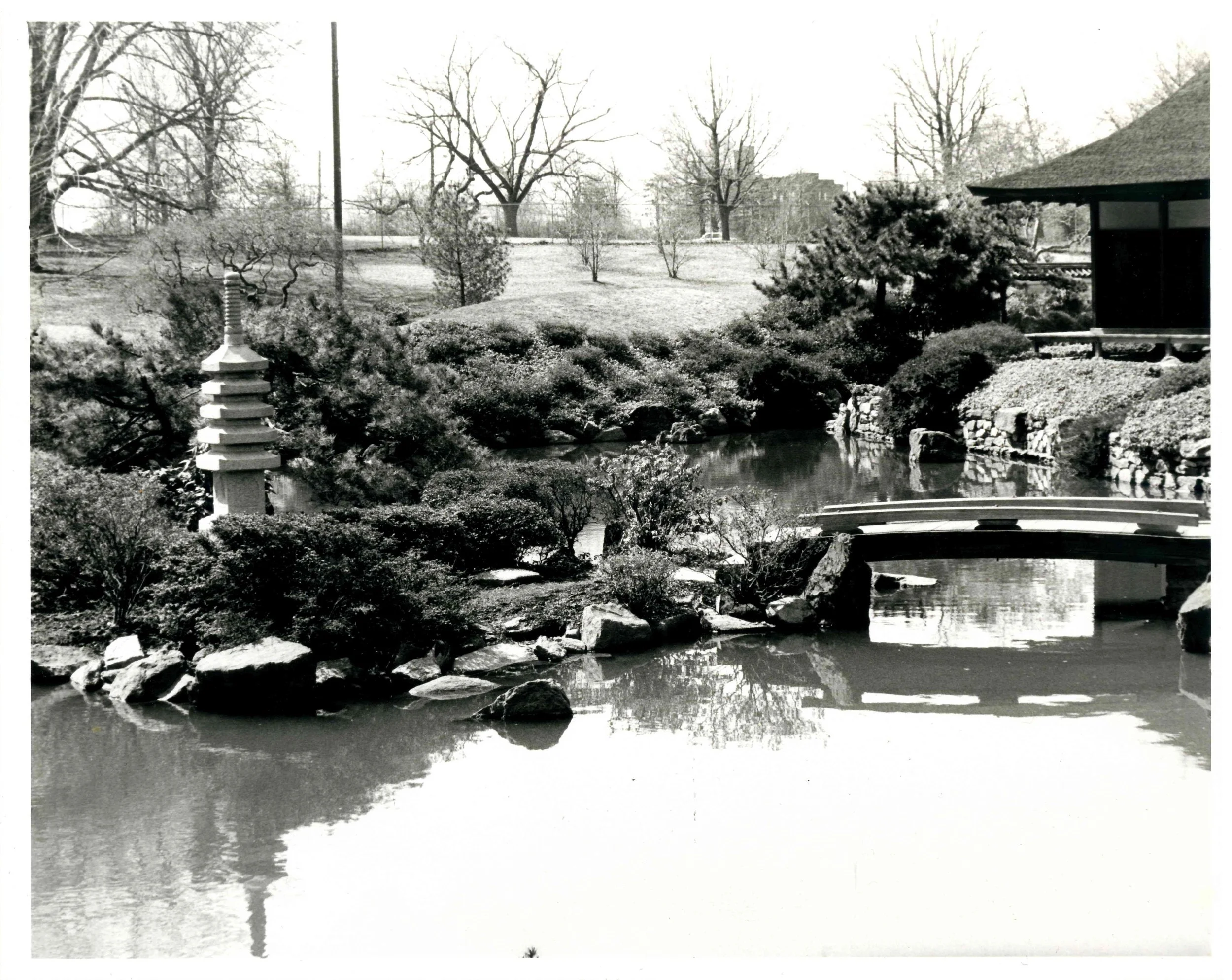

Photo: The garden at Shofuso, circa. 1961-3. From the JASGP archives.

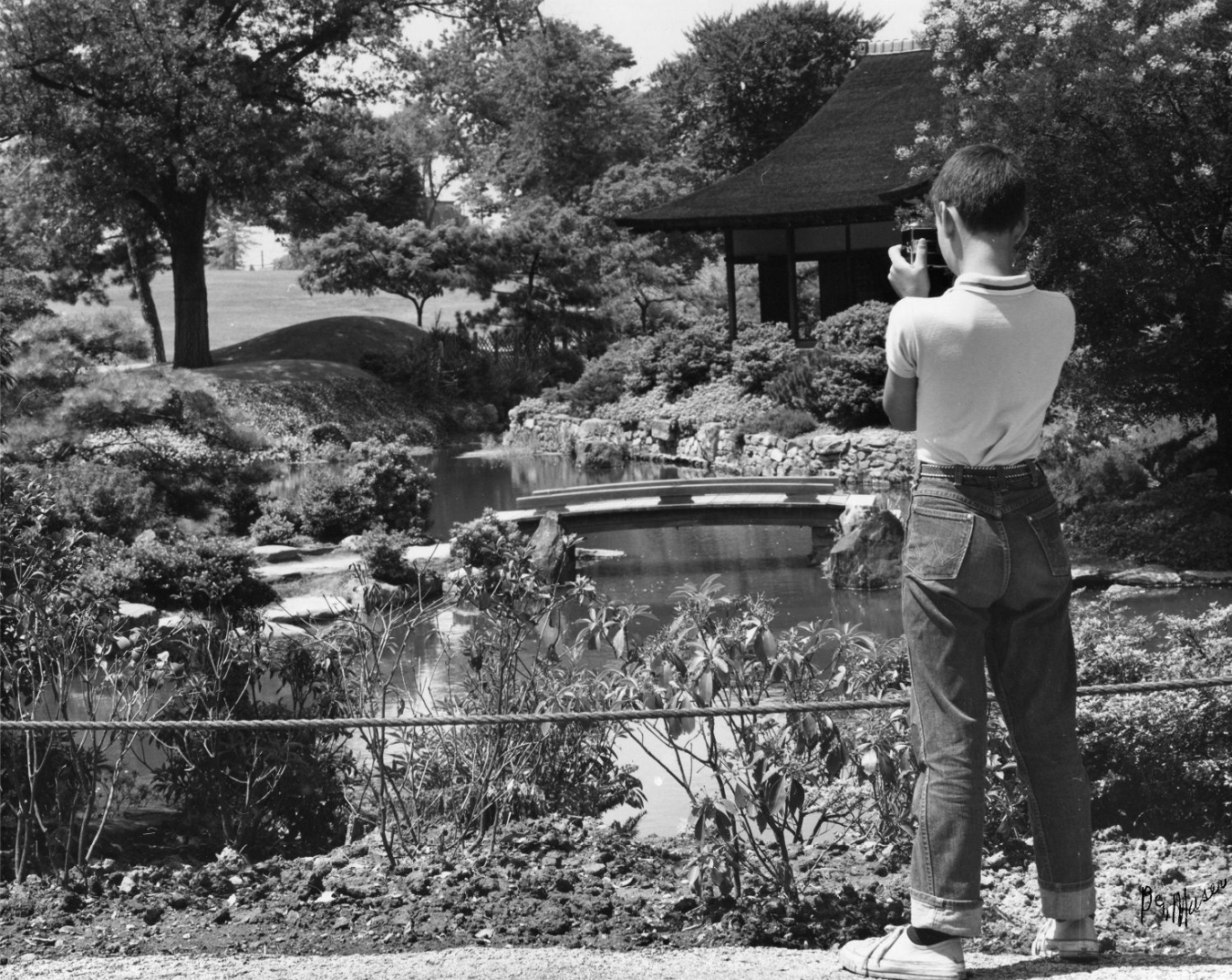

Yoshimura and Sano were equally excited about the prospect of a larger, more vibrant site. The efficacy of shoin-zukuri architecture hinges on a successful relationship between house and garden. Together, they saw this as an opportunity to create an even more striking integration.

The site at Fairmount Park is seven times larger than their tiny lot in New York, and already had the remnants of an elegant stroll garden. Working with a local landscape architect, David Engel, Sano integrated the existing lotus pond and temple garden into his designs.

Like Yoshimura combined three architectural styles, Sano synthesized three distinct gardens into one. Out front, the tsukiyama (hill and pond garden) composes the vast, elegant views from the veranda. On the way to the tea house, visitors are slowed down as they walk on the staggered steps of the roji (tea house garden), encouraging a quiet contemplation before the tea ceremony. Walking through the house, one encounters the tsubo-niwa (courtyard garden) with its dribbling stream linking the Schuylkill to the pond.

Unfortunately, Sano could not secure the funds to finish his designs, and Engel was forced out shortly thereafter. Though initially unfinished, the garden has since undergone excellent preservation and restoration over generations of caretakers here in Philadelphia, uniquely loved by each and every one of its tenders.

Vandalism & Restoration

Author photo. From July 2025 Tanabata Festival at Shofuso

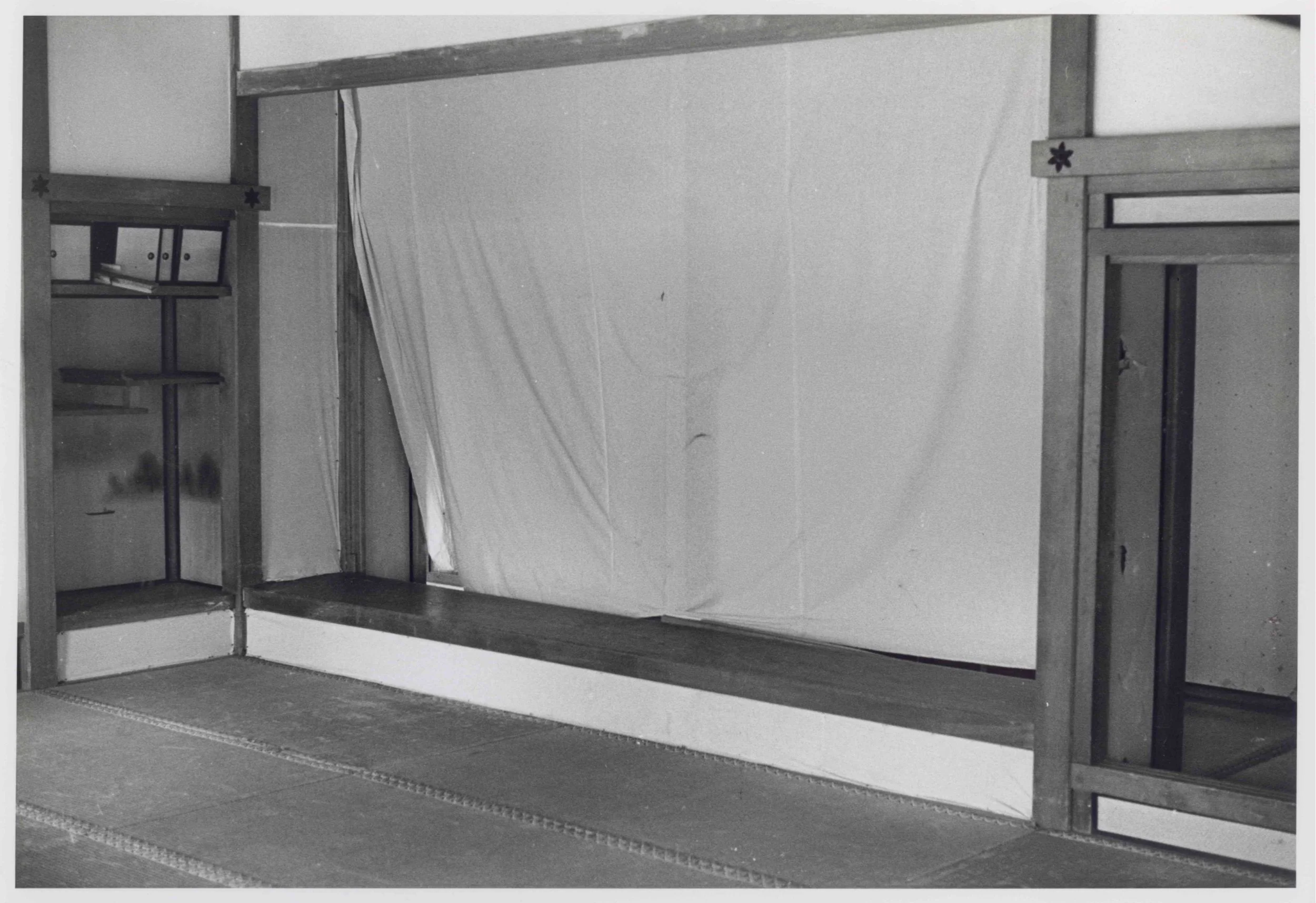

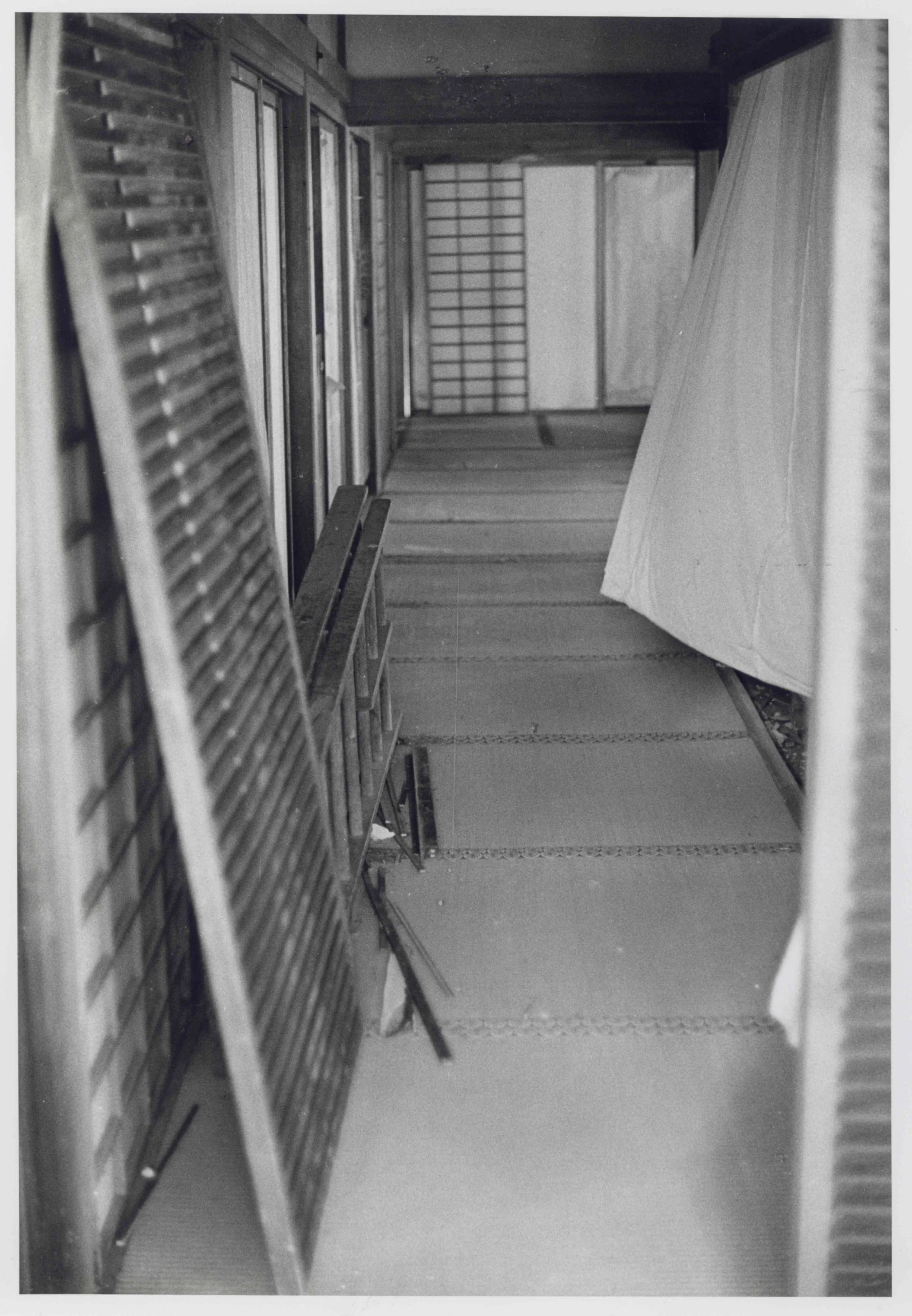

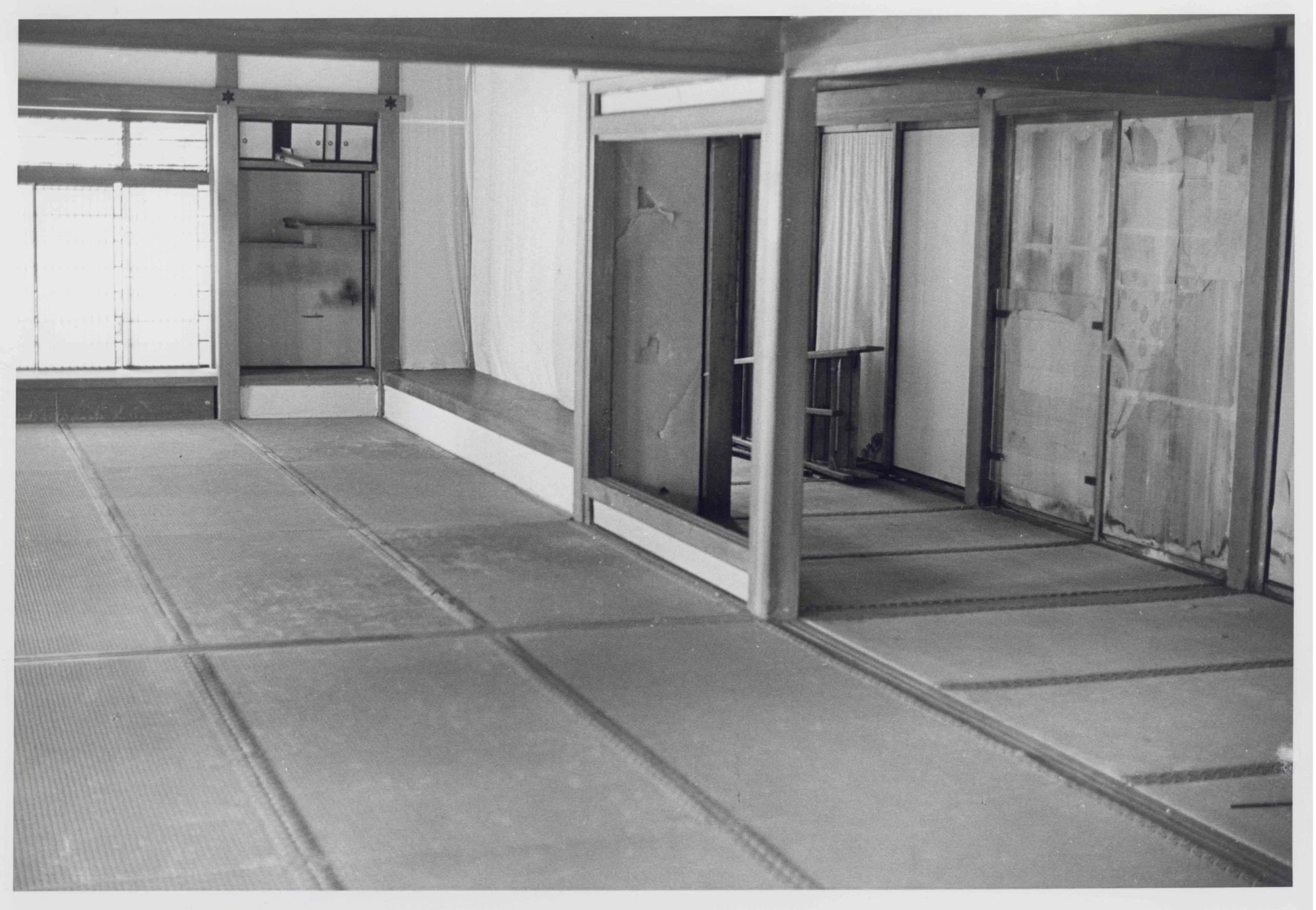

Much like the Nio-Mon before it, the Park could not afford to protect or care for its Japanese asset. It very quickly fell victim to a string of vandal attacks throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. The rice paper shoji screens were torn through, what little ornament decorated the house was destroyed, and in one particularly heinous attack, a small fire was set inside. Worst of all, the elaborate Nihon-ga paintings by Kaii Higashiyama were decimated. After all of these break-ins, all the Park could afford to supply was a meager chain-link fence.

Conditions at the house worsened until the Japanese government threatened to repossess Shofuso in 1974. With the 1976 Bicentennial quickly approaching, the Park was very interested in restoring the house to its original glory. Negotiations stalled with the ‘76 Corporation, in charge of the citywide celebration, who claimed that the Japanese Philadelphian community was too small to warrant an investment. Instead, a contingent of Japanese industry generously gifted $500,000 for its restoration as a 200th birthday gift to the US.

Junzo Yoshimura, now in his late 60s, returned to Philadelphia to oversee the much-needed renovations. Working with architect George Gentoku Shimamoto, the team completely restored the house, replacing burned tatami flooring mats and putting up blank white screens where the painted ones once hung.

TBD