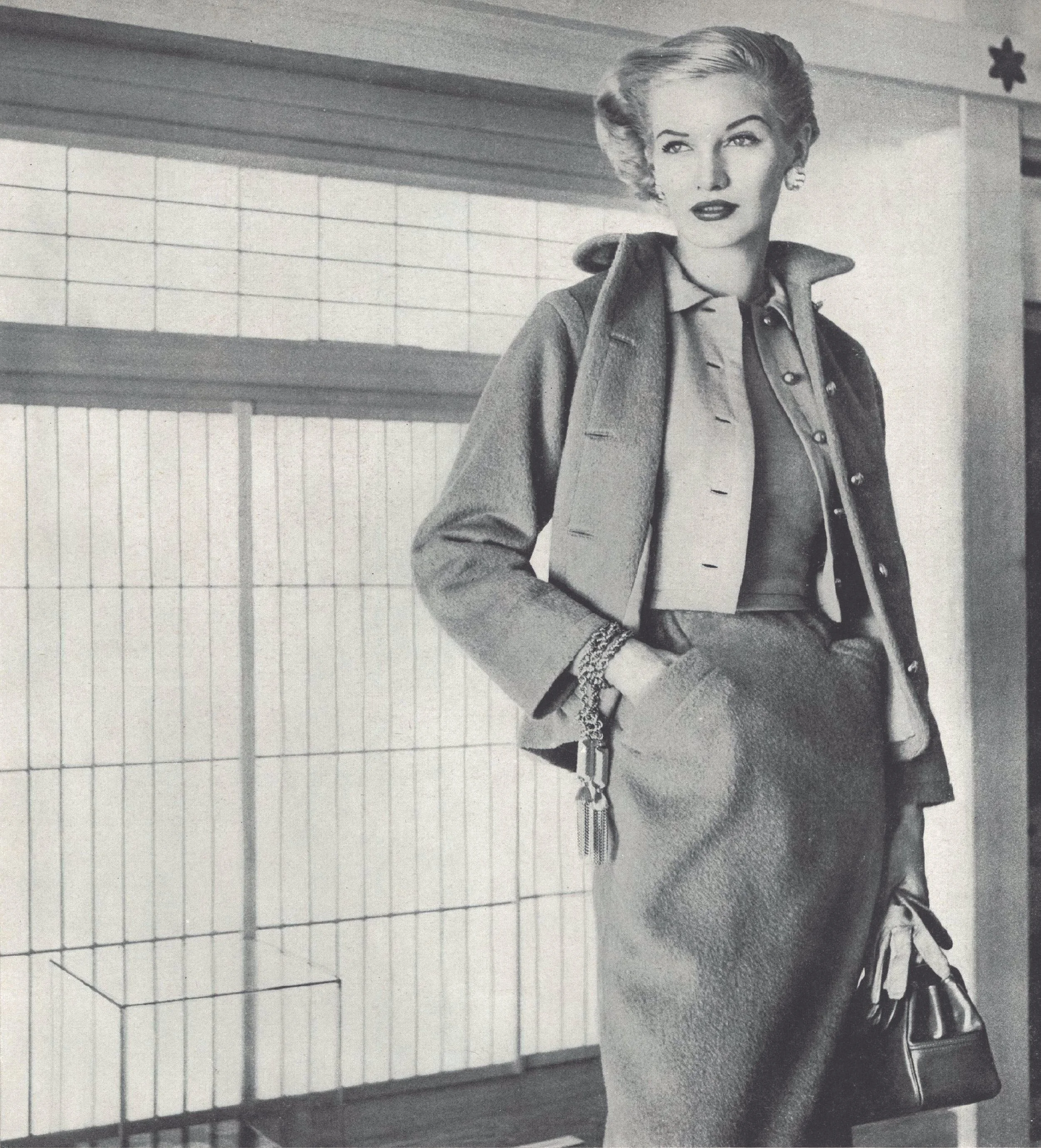

MoMA EXHIBIT #559

A Third House

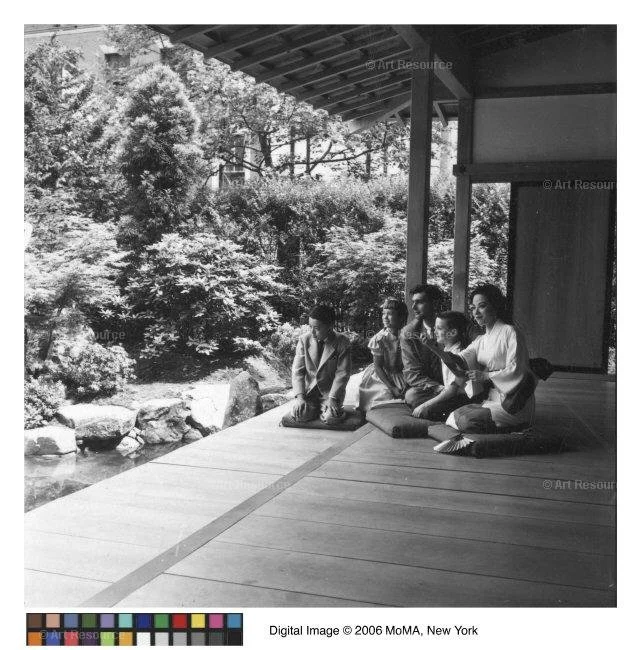

Photo: "Installation view of the exhibition ‘Japanese Exhibition House’” by Ezra Stoller for the Museum of Modern Art, 1954. No. IN559.35 at MoMA

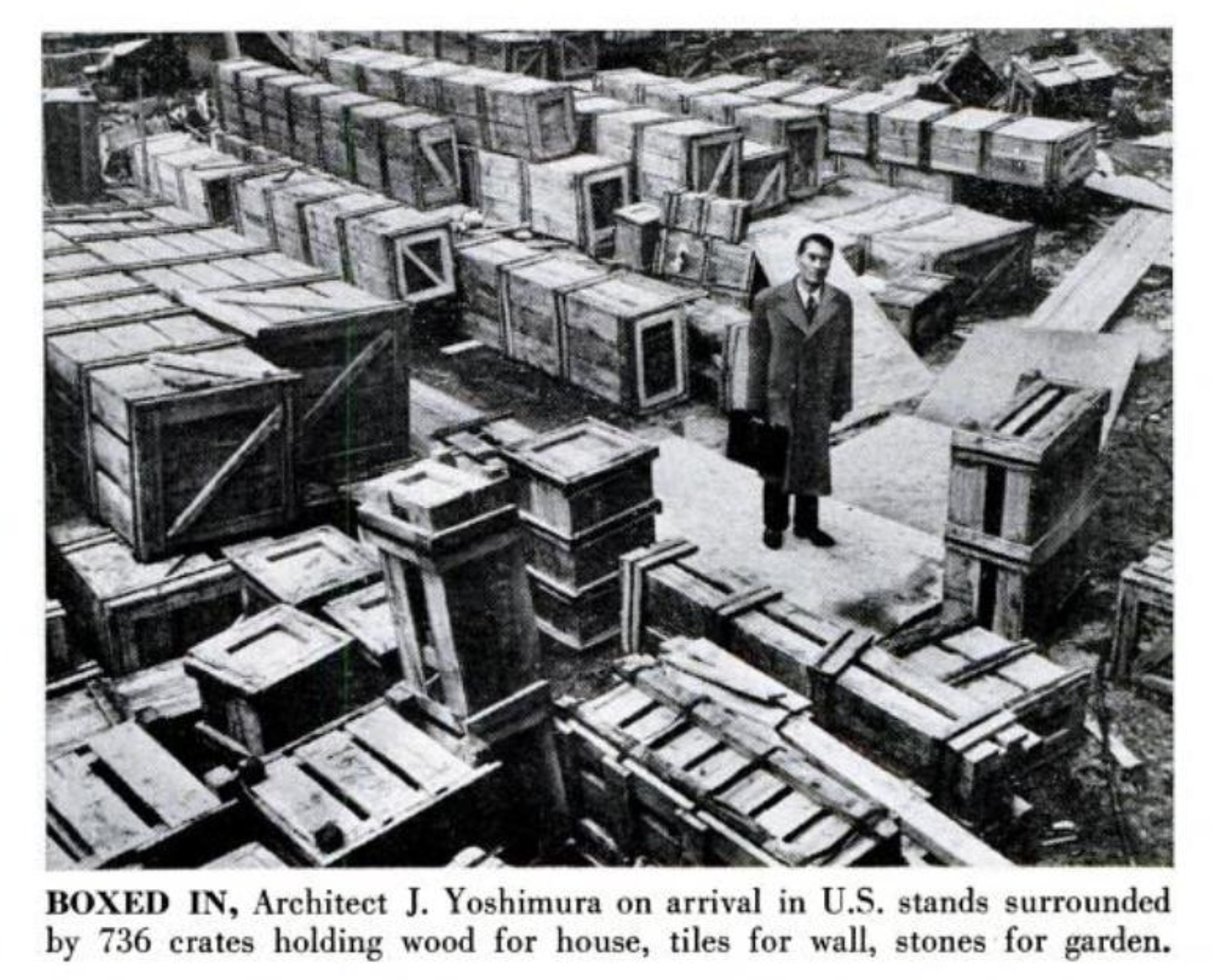

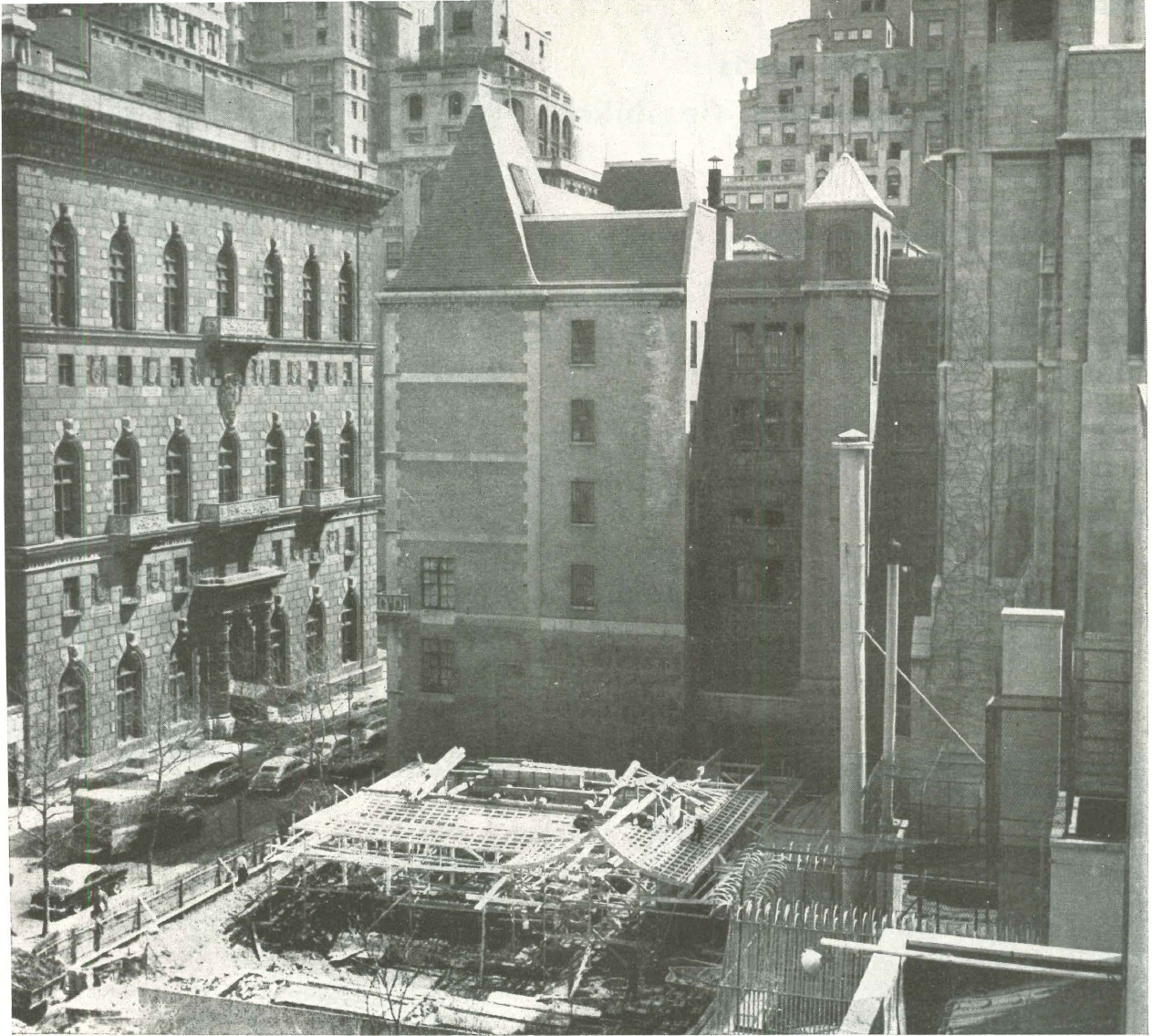

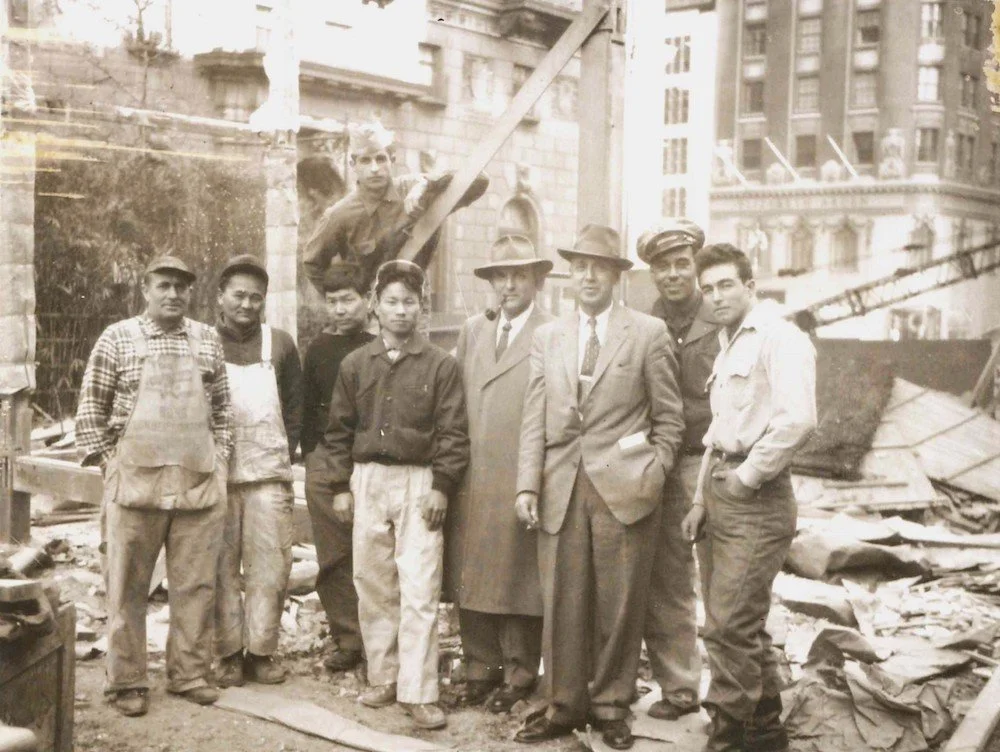

In New York City, the Museum of Modern Art had just concluded its second House in the Garden installation, featuring full-sized examples of Modernist houses. The first two featured American architects Marcel Breuer and Gregory Ain, but new curator Arthur Drexler and longtime patron John Rockefeller, III, wanted to expand their repertoire. Drexler wanted to highlight the “unique relevance” to the Modernist movement that traditional Japanese architecture effortlessly encapsulated.

Rockefeller introduced Drexler to the I-House architects, and were inspired by Yoshimura’s familiarity with both traditional architecture and modern sensibilities, as well as his experience designing in America. The team toured Kyoto to find inspiration for the exhibition house and were taken by the “pure light compound” at Onjoji Temple, which Drexler found to be “most representative of the traditional Japanese architecture” he wanted to feature.

Although Shofuso was designed and constructed in the 1950s, it is an honest representation of classical Japanese architecture as it would have appeared in the 17th Century. Drexler was insistent that they make no concessions to modern amenities, lighting, plumbing, glass windows, and more. Shofuso is not a carbon copy of the buildings in Kyoto, but rather a spirited homage, continuing in the line of utsushi from its Kyoto predecessors.

Video from construction at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. From JASGP “Okaeri Okamura Footage 1954 1957” on YouTube

Exhibition video from the Museum of Modern Art. From MoMA “A Japanese House (1955) | MoMA FILM VAULT SUMMER CAMP” on Youtube

Multiple Purposes

Photo: Sonny Fox (right) is joined by Yoshioko “Shirley” Yamaguchi at the Japanese Exhibition House to tour Pud Flanagan and Ginger MacManus for CBS’ Let’s Take a Trip on June 30, 1955. No. P43209B at the Temple University Libraries

It was not even a full decade after World War II devastated the Pacific and nearly irrevocably damaged US-Japanese relations. Now, in the shadow of the Cold and Korean wars, the United States was committed to “consolidating” its relationships throughout Asia. Rockefeller was an influential advocate for amnesty between the US and Japan, and his wife, Blanchette, accompanied him on reconciliation envoys to Japan. Because of this eminent couple and their dedication to the Japanese Exhibition House at MoMA, the Japanese government gifted Shofuso to the United States as a symbol of the renewed relationship.

Drexler was more interested in the architectural salience of the Japanese House. Shofuso is mostly designed as a shoin-zukuri structure, built for Japan’s educated elite, requiring a “disciplined esthetic and wider technical range” than other Japanese styles. This was well within Junzo’s wheelhouse. To him, shoin-zukuri was already in and of itself Modernist, with its “profound absence of clutter,” highlighting its “space, light, air, openness of plan, and lightness of appearance.” Drexler was determined to create the illusion that one had teleported to Japan, but Yoshimura was much more cost-conscious. “I want the water and the plants!” Drexler asserted. When the budget got too tight, Blanchette Rockefeller personally wrote a check.

Today, Shofuso still stands as the physical representation of US-Japanese relations, as well as architectural inspiration. By the end of the New York exhibition, Drexler was proud to say that “just about every important architect had come to study” at Shofuso. Now, the Japan America Society of Greater Philadelphia carries out its third purpose: Japanese cultural exchange for all Philadelphians.

The House

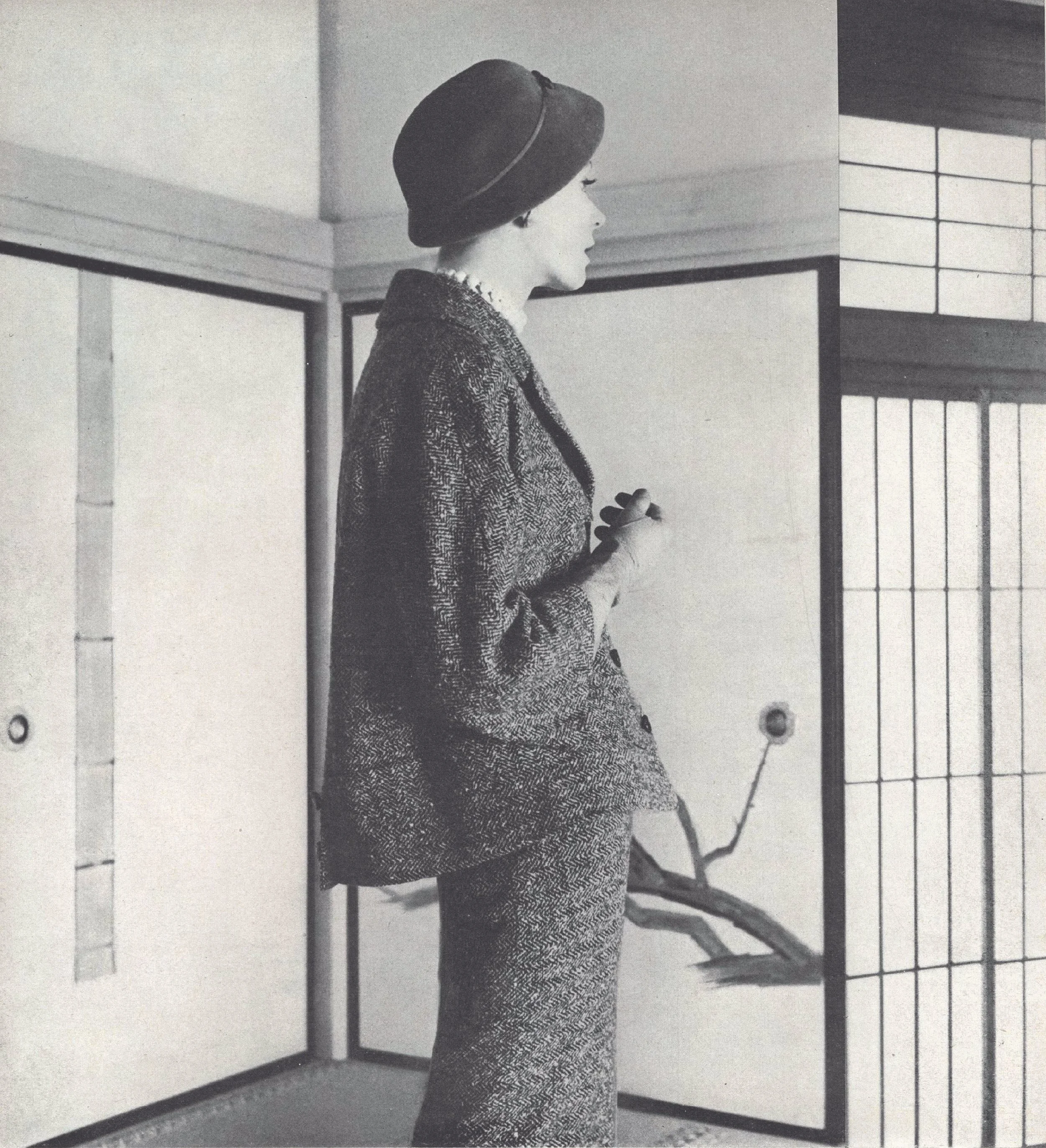

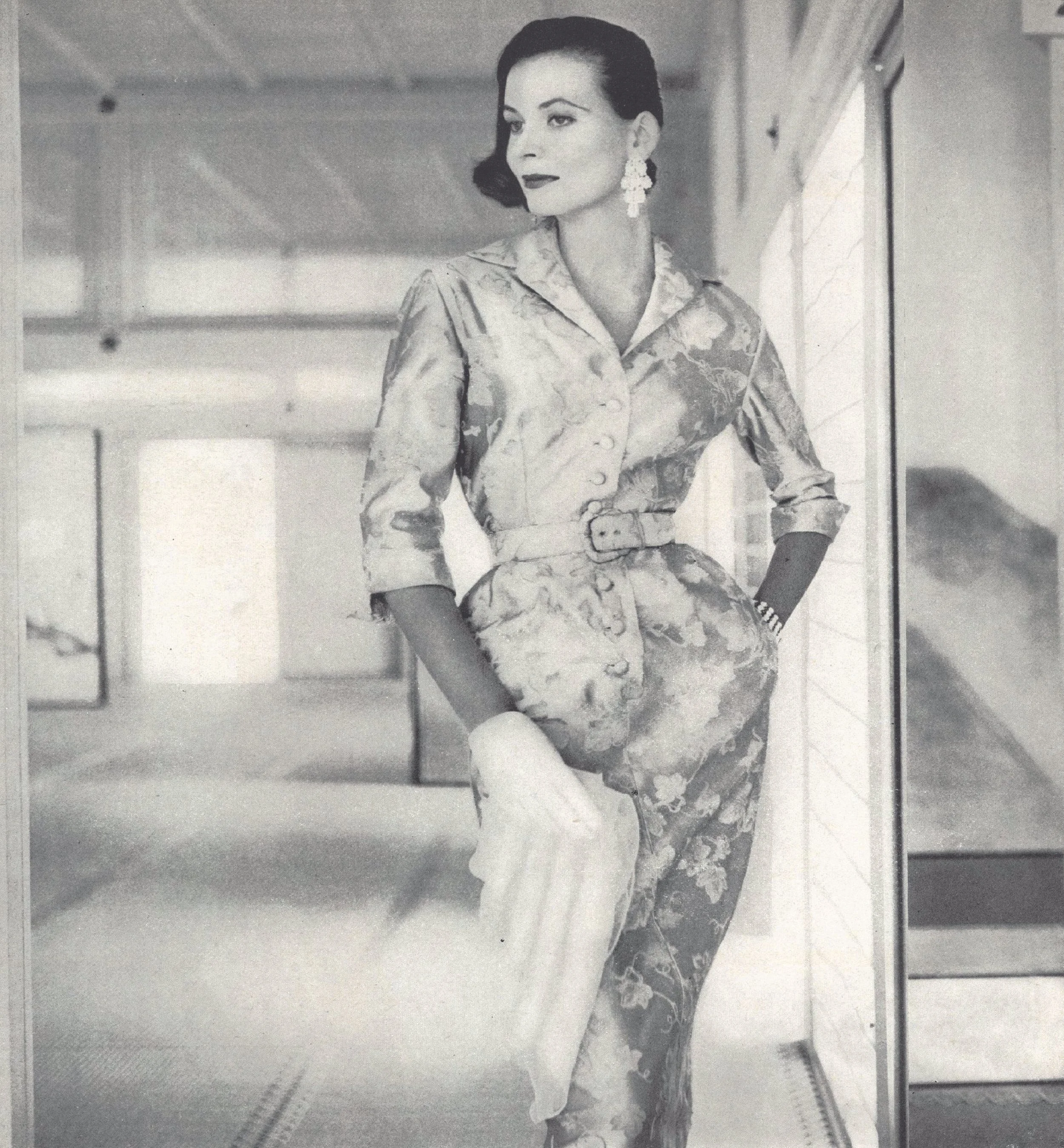

Photo: "Installation view of the exhibition ‘Japanese Exhibition House’” by Ezra Stoller for the Museum of Modern Art, 1954. No. IN559.42 at MoMA

Shofuso is an exquisite example of shoin-zukuri architecture made popular throughout the 14th to the 19th centuries. Named for its shoin (desk) in the main room, these homes were designed for Japanese educated elite who would need such tables to write letters, official documents, sutras, and stories. Scholars, magistrates, and priests populated shoin-zukuri homes throughout Japan.

Yoshimura spared no expense or effort in the design of Shofuso. Shoin-zukuri homes of course require the tsukeshoin (built-in desk), but also often contain a number of other architectural features, such as the tokonoma (sacred shrine), chigaidana (staggered shelves), and chidaigamae (decorative doors). In Japan, it is rare for a home to have all four elements in one home, but you can see all of them at Shofuso.

In all, Shofuso melds together three distinct styles: Shoin-zukuri in the main home, while across the courtyard is a Sukiya style teahouse. Sukiya-zukuri developed alongside the tea ceremony, with its built-in sunken hearth and commitment to natural details. Towards the back of the house is the Minka style kitchen, featuring an earthen floor. The three distinct styles come together under one roof to form a cohesive home.

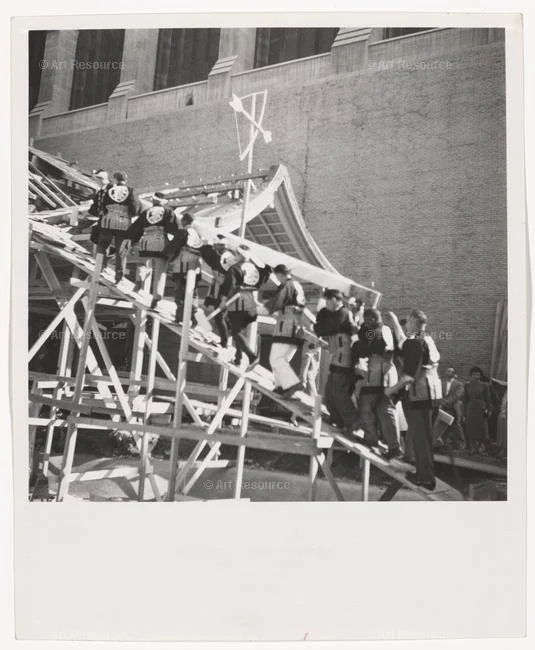

The roof is distinct as well. Made from thousands of pieces of hinoki bark taken from Japan’s national forests, the elegant roof is Shofuso’s most identifiable feature. To the Japanese, the roof is the true beauty of a building. Though there are other Japanese buildings and tea houses throughout the world, Shofuso is the only one outside of Japan to be blessed with a hinoki roof.

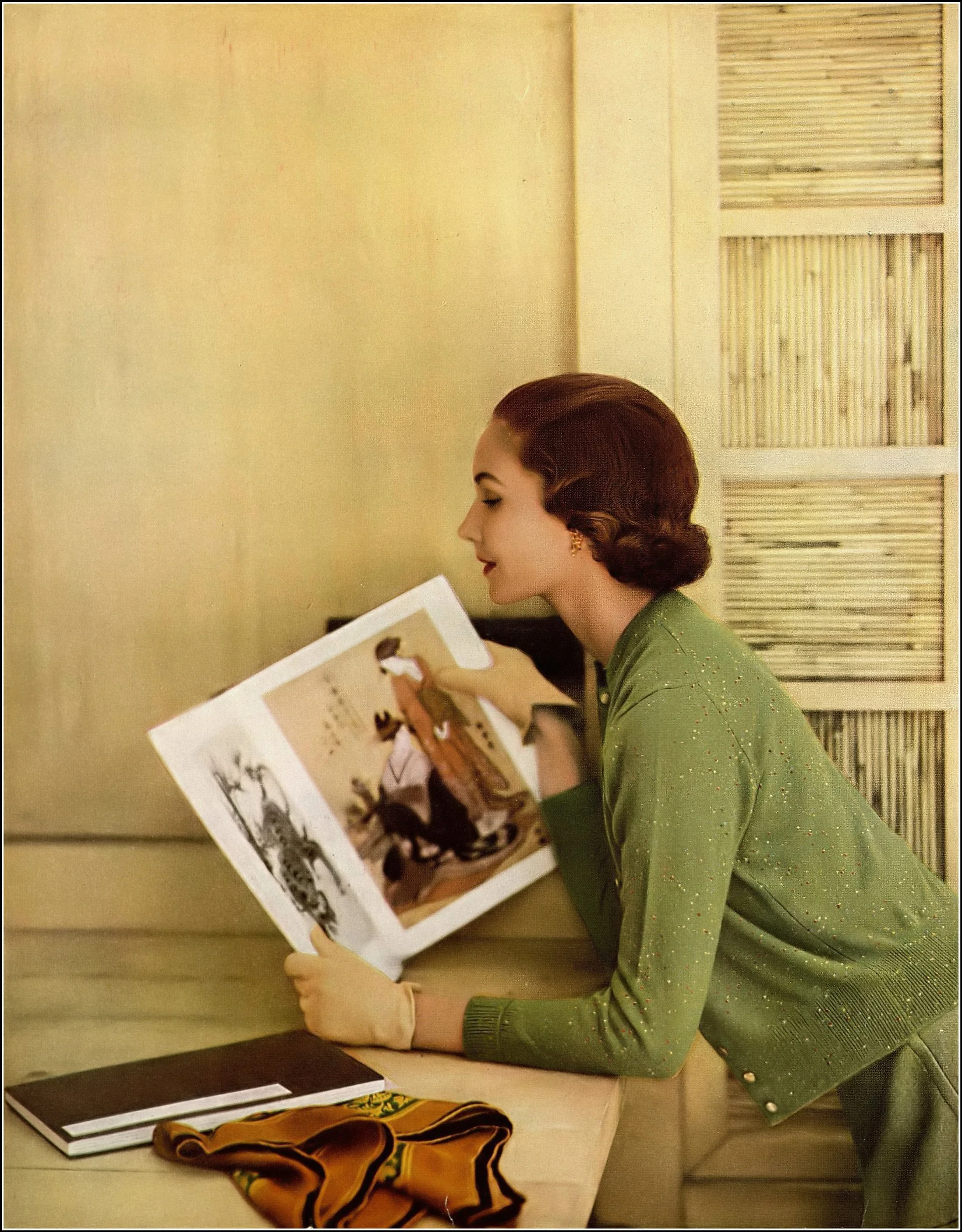

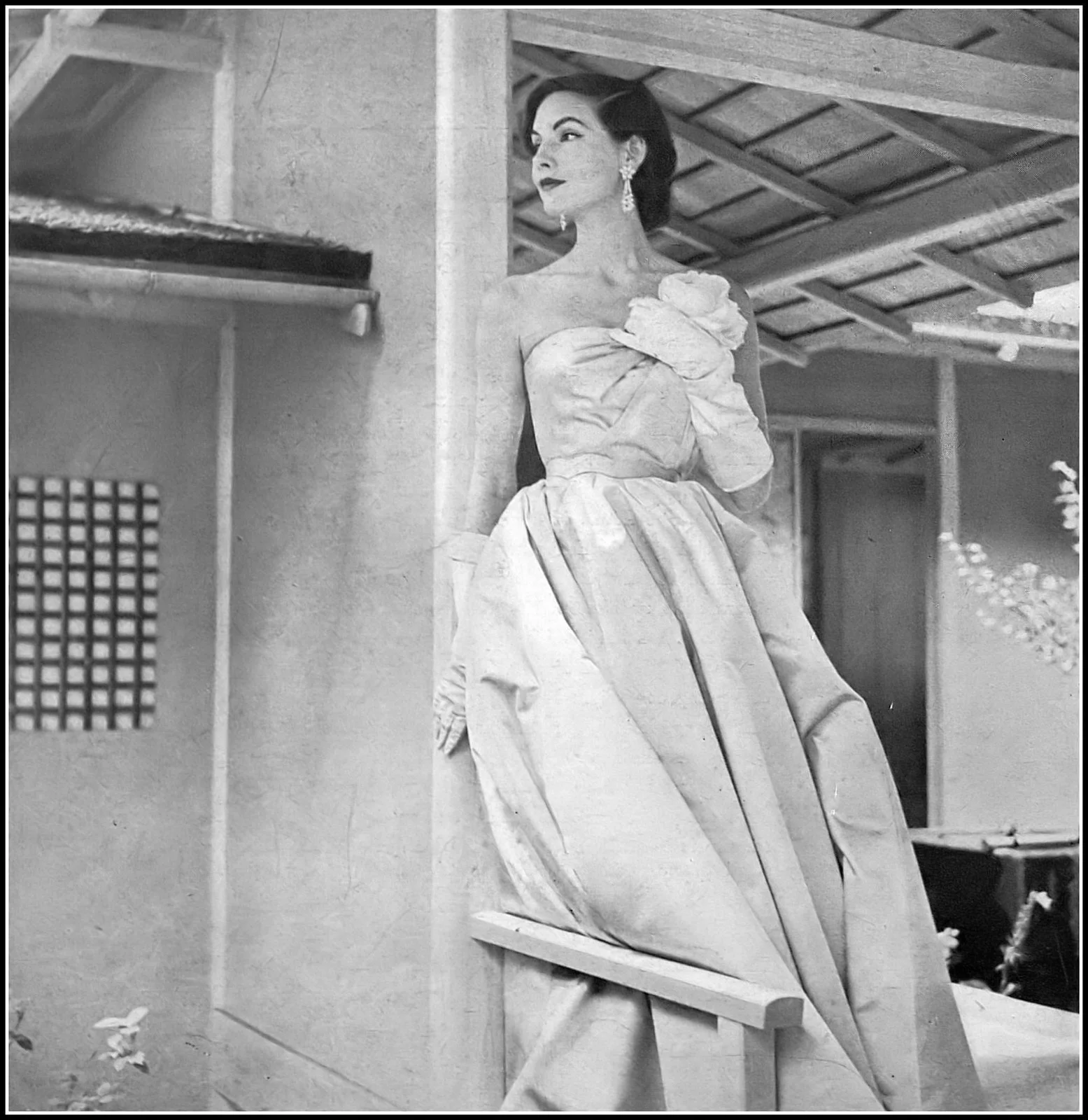

Click on any of the magazine covers to explore the feature article

"The Japanese had some of our best ideas - 300 years ago" from House and Home, June 1954, Vol. 5, pages 136-141

"House With a Spirit" from Newsweek Magazine, July 5, 1954, Vol. 44, No. 1 page 50

"Japan Hit: New Yorkers flock to an Oriental House" from LIFE Magazine, August 23, 1954, Vol. 37, No. 8, pages 70-74

Reception

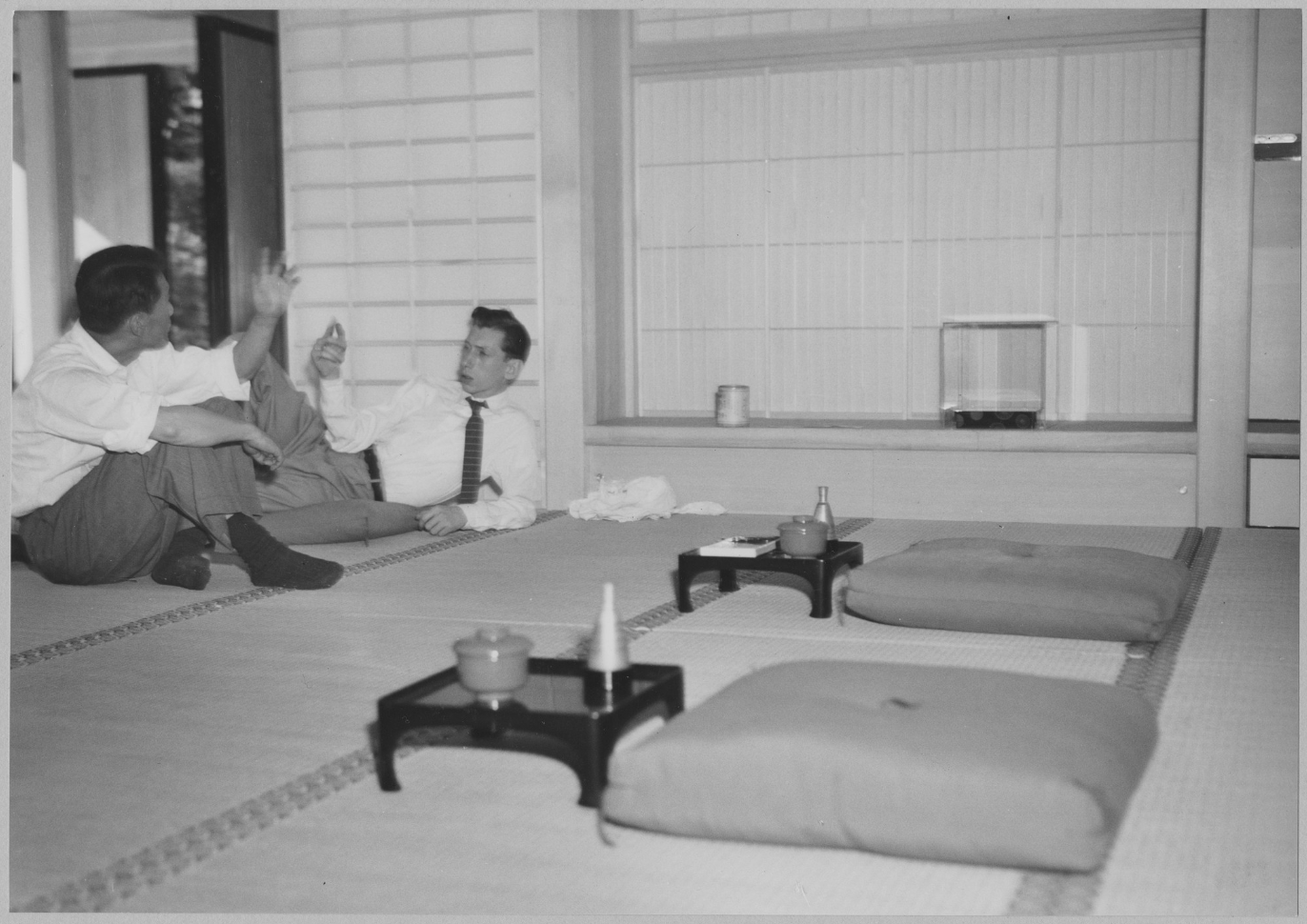

Photo: "Japanese House in the Museum Garden: Showing architect, Mr. Yoshimura discussing plans with Curator of the Architecture Dept. Arthur Drexler” by Ezra Stoller for the Museum of Modern Art, 1954. No. IN559.11 at MoMA

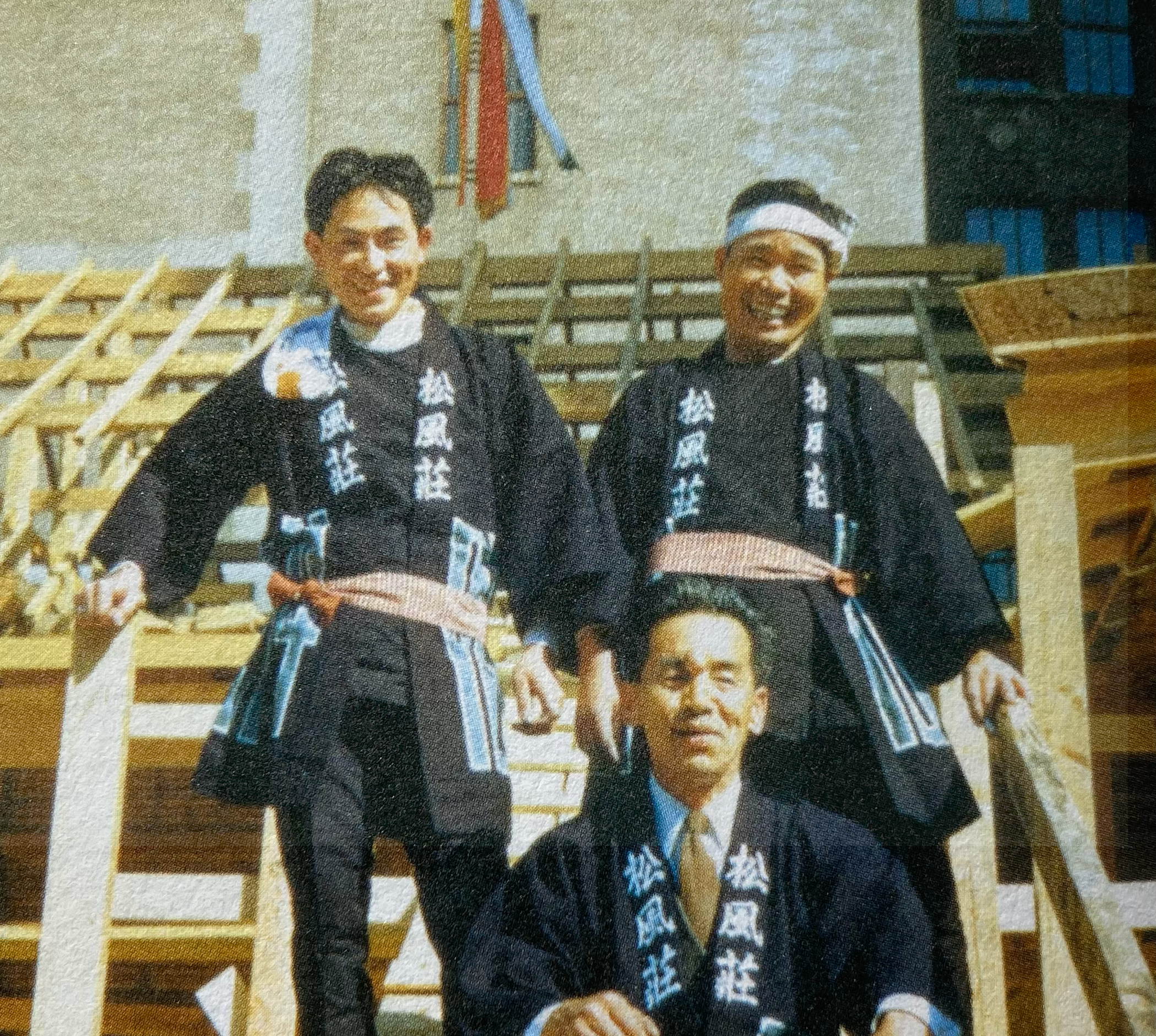

The Japanese Exhibition House opened to the public on June 20, 1954, to an astounding 1,356 visitors. Even the construction, much like the buildings at the 1876 Centennial, had stirred up quite the buzz. Before its official opening, Drexler bestowed the project its name, Shofuso, meaning “Pine Breeze Villa.”

It may be difficult to imagine this quiet, serene house and garden in the middle of downtown Manhattan, surrounded by bustling streetscapes and skyscrapers, but Yoshimura and famed landscaper Tansai Sano created an intimacy with the space down at ground level with its exquisite views from the veranda into the garden.

Over its two years in New York, the house welcomed over 200,000 visitors, nearly three times more than the two previous exhibition houses. Life Magazine called it New York’s “most popular summer rendezvous.” New Yorkers were enchanted by its spatial simplicity, but one woman, interviewed by the New York Times, asked “Where do you put the TV?” Here, we prefer to embrace the quiet serenity and soft bubbles blown by the magnificent koi.